|

|

Letter Writing

[License to Crenellate]

[Letter to a Patron] Family Papers: [Introduction] [Patent of Arms] [Jousting Cheques] [Birthbrief] [Impresa] [Festival Book] [Family Tree from Heraldic Visitation] [Roll of Arms] [Armorial]

Books or Collected Works:

[Book Production]

[Three Bestiaries]

[A Crescent Isles Herbal]

[Royal Commonplace Book]

[Commonplace Book] [Chapbooks]

[The Tales of Canterbury Faire]

[Concertina Quote Booklet]

[Bookmarks]

[Book Covers] Single-Sheet Material: [Gypsy Proclamation] [Banns of Wedlock] [Collosal Squid Broadsheet] [Dickon's Lament] [Broadsheets] [Playbills] [Roundels] [Ecce Ildhafn]

Event-related Printing:

[CF Newsbooks]

[Banco di Don Julio shares]

[Livery Companie Proclamation and Charter]

[November Crown Tourney ASXLIV]:

[Vade Mecum]

[Crown and King]

[Flags and Water Bottles]

[Antiphon]

[Crown Broadside] License to CrenellateWhen my lord and I became Baron and Baroness of Southron Gaard (AS39), we felt it necessary to throw ourselves upon the merciful nature of King Stephen and Queen Mathilde to correct an error of omission on our part. We had to confess that, for the past dozen years or more, my lord and I had been living in an adulterine manor, that is, we had been dwelling in a manor house that had been crenellated without royal license. Thus we begged a Letter Patent to legitimate the turrets and crenellations of the Hermitage, our home.

Over the years we petitioned a number of Crown, with various pleas verbal and written. The letter to a patron did nicely in the A&S Competition category, but didn't advance the cause any. When Their Excellencies of Ildhafn, Inigo and Cecelia, stepped down in AS43, we apprised Their Majesties of our forthcoming departure from the baronial seats and begged that our manor house be legitimated that we be protected once we were no longer the Crown's representatives in our barony. And so it continued. For some odd reason, They all wanted to take it under advisement... Success!At Royal Court at Canterbury Faire in AS45, I was called before Their Majesties Gabriel and Constanzia and advised that as Warden of the King's Livery Companie I really should not be breaking the laws of the land, and thus They would grant the license providing certain fines were paid for the years of non-legitimate crenellation display. I had been taken by surprise and had no funds upon my person, whereupon two individuals of the mercantilely replete Barony of Ildhafn, suspiciously seated in the front row, leaped forward to pay on our behalf. Their Majesties graciously accepted this, noting only that They could not possibly set Their seal to the license until the good burghers were paid....

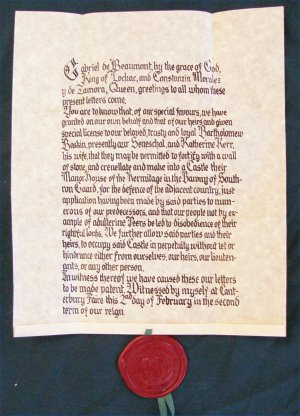

Negotiations continued through the event. Mistress Roheisa was kind enough to gift us some gold angels to pass into the hands of the Ildhafners, and we scored a "straugne and maruellous fruite" which was clearly magical in nature (ie a particularly odd-looking marrow) to add to the payment. Master Willam and Mistress Katherina pronounced themselves satisified that the debt had been paid and we were given permission to set seal to the licence, so carefully and quickly scribed by Master Iarnulfr. (I should have been more suspicious earlier in the day when Mistress Katherina asked me to demonstrate how to fold a writ....) The license differs a little in wording to that presented so many years before (see below), but is a fine example of its kind: Gabriel de Beaumont, by the grace of God, King of Lochac, and Constanzia Moralez y de Zamora, Queen, greetings to all whom these present letters come. Woohoo! I do like that "not by example..." clause. Royal LicensesIn 1091, William II and his brother Robert of Normandy drew up a joint document, Consuetudines et Iusticie, reporting on the laws and customs of England and Normandy, noting that castles could not be constructed without express royal permission. This royal grant later became known as a Licence to Crenellate and was required for private fortifications when either building a new castle or fortifying a manor house by crowning the walls and towers with battlements.

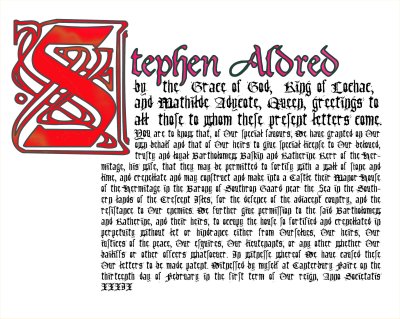

Many licenses are recorded in The Calendar of Patent Rolls (Henry III to Elizabeth), and many examples can be seen on display in such manors to this day. Some of these were granted in advance of such work, others were licensed retroactively - if you erected a castle without a license, it was known as an adulterine castle until such permission was forthcoming and the works legitimated. The licensing procedure began with the appeal to the King, usually at a court. A royal assent would be noted by the King's secretary and recorded on the Patent Roll. A warrant under the King's Signet Seal would be sent to the Keeper of the King's Privy Seal, who would in turn send a warrant to the Keeper of the Great Seal and a receipt to the Keeper of the Signet Seal. The Keeper of the King's Great Seal would then send a receipt to the Keeper of the Privy Seal and order the preparation of the Licence to Crenellate in the form of a Letter Patent. The Licence would be sealed with the Great Seal and delivered to the licence-holder Such licenses were issued throughout many reigns: Edward III issued 181, Richard II 60; from then on the licenses petered into the single digits, with Edward IV granting just 3. These were issued in the form of a Letter Patent - an open letter noting permission to fortify a specified building granted to its holder (often mentioning their spouse), along with a guarantee that such a privilege would last in perpetuity. Here is one example of a Licence to Crenellate, issued for Allington Castle in 1282, by Edward I: Edward, by the grace of God, king of England, Lord of Ireland and Duke of Aquitaine, greeting to all to whom these present letters come. Another example is held by Hemyock Castle, granted by Richard II n 1380. The wording for our license is based on these examples: Stephen Aldred, by the grace of God, King of Lochac, and Mathilde Adycote, Queen, greetings to all to whom these present letters come.

These licenses were typically written in legal Latin and left open, as they were public documents intended to be viewed. As a public proclamation, it starts with a salutation from the King to the reader, the forerunner of the modern "to whom it may concern". They were not usually signed, but authenticated with the King's seal, usually with a coloured cord attaching the seal to the paper. Dr Diane Tillotson, in Medieval Writing, History, heritage and Data Source, notes that, in general, such letters were not highly decorative, the emphasis being on a neat, legible hand that did not distract from the business under consideration. The only calligraphic extravagance appears to be the occasional production of fanciful and curly capital letters of rather spidery form at the head of the document. The actual layout of the license has been based on examples of Letters Patent held by the British Library, one by Edward IV (a 1472 grant of arms) and a later one by James 1 (1610, creating his son Henry Prince of Wales). These are more decorative than the actual License of Crenellate I examined at Oxburgh Hall, but similar in general layout. The font used is Tfu Tfu, a freely available font designed to look like a hand-lettered text, complete with smudging. This seemed more appropriate than the more legible fonts, and certainly is much more readable than the Courthand occasionally used for such material. This font, like many, lacks a long s, so I adapted one from a similar font (WW2 Blackletter). The text was run through Jeff Lee's adaptor to check correct usage of the long s and convert j to i and u to v. The capital was chosen as one roughly approximating the style of the British Library examples cited above, with a small amount of handwork added. Letter to a Patron: Substance, Structure and StyleThe ASXVI 12th Night Arts and Sciences competition topics included a letter for a patron, so it seems like a good chance ot kill two birds with one stone, and follow up the plea regarding the license to crenellate. So I ended up writing a letter to Duke Ædward Stædfast asking for his assistance in interceding with the King of Lochac over the long-outstanding petition. Here is the text of the letter in period spelling and usage, though in deference to the vagaries of online reproduction, I have changed the thorn symbols over to the more commonly available th. To the right hyghe and myghty prince and right especiall lord Dwke Ædward do we recomaund ourselfs to yowre gode lordshep, besechyng youre lordshep that ye take not to displesauns thow we write you as we here say: The terms and usage in the letter have been based on extracts from and following the style of the well-known collection of Paston letters, produced by that family over the course of 80 years or so (ca 1425-1503). It is clear from this collection that English was considered an acceptable language for communication of all levels, whether writing to a spouse or a sovereign. According to Tillitson, and based on examples within the Paston collection, such letters were not an uncommon way of bringing matters to the attention of the king for he or his officers to deal with. I would have liked to have put it into Scottish usage to suit my persona, referencing the material in Donaldson and Yeoman's collections of written works, but the bulk of their material related to treaties, legislation and ambassadorial reports. In addition, Scots, as a written dialect in the mid-1500s, is less intelligible than 15th-century English to the modern eye. Nonetheless these collections have proven useful in providing more material to gain a feeling for how correspondence was typically structured and the rhythm of the type of language used. Splicing pieces of letters together from examples of approved format was a very common practice throughout period, and one highly recommended by Lawrence of Aquilegia.in the 1300s in his treatise The Practice and Exercise of Letter Writing. Use of form letters dates back to at least the 6th century, and various model books and manuals on rhetoric and correspondence were available throughout Europe and in regular use for the following millennia and beyond (Perelman; Mathewes). A surprisingly large number of letter-writing manuals were popular across 200-300 years, including Lawrence's and that of Hugo of Bologna (Principles of Letter Writing), as well as the Dictaminum radii and Breviarium de dictamine produced by Italian monk Alberic. The ars dictaminis sought to develop the art of practical letter-writing, and a class of professional dictatores developed to provide letter-writing services. This very formulaic approach dwindled in popularity during the 1500s when a more spontaneous, humanistic style came into vogue, particularly for personal correspondence. Despite the change in fashion, much of the older ars dictaminis conventions remained, particularly with regard to the structure and rhetorical nature of the communication (Mathewes). Many of these conventions would be familiar to the modern letter-writer, with a well-composed letter consisting of the following:

SalutationsThe letter to a patron should start with a suitably unctuous opening, allowing the writer to address the patron and establish their relative positions on the social scale. This has been recognised as an important way to start any correspondence from very early times, with Cicero defining the exordium as a means of making the recipient feel "well-disposed, attentive and receptive" to the writer (Perelman). As Dr Diane Tillitson writes, in Medieval Writing, History, Heritage and Data Source, of petitions to the King: The initial clause tends to a rather grovelling tone, as the petitioner beseeches meekly and sometimes refers to himself as humble or poor. The whole tone really does not go well with modern egalitarianism, but was designed to emphasise the elevated standing of the king and appeal to his mercy, compassion and honourable sense of justice. Hugo of Bologna has numerous examples of suitable salutations to be used when writing to the Pope, the clergy, assorted nobleman and princes, as well as close friends and associates. My letter's opening begins in a similar vein to that of the rather cautious 1454 letter from John Paston to the Earl of Oxford: Right worshipful and my right especial lord, I recommend me to your good lordship, beseeching your lordship that ye take not to displeasance though I write you as I here say... Or, as the original has it: Right wurchepfull and my right especiall lord, I recomaund me to yowre gode lordshep, besechyng youre lordshep that ye take not to displesauns thow I write you as I here say Early commentators, such as Hugo of Bologna, split the classical exordium into the salutatio and the capitatio benevolientiae, stressing the importance of securing good will as a follow-on from the initial salutation (Newbold). This is achieved by emphasising the good character and renown of the recipient and the humble nature of the writer. It was also common practice to include a reference to the relationship between to two or their shared history or to refer to the accomplishments of the writer, though there is a need to be careful with regard to the latter lest one overstep the bounds of establishing a suitable level of humility. As Hugo advises: we should devise our letters in such a way that whenever the humility of the sender or the merits of the recipient are advanced at large in the salutation, we should either begin the rest of the letter immediately with the narration or with the petition, or we should point out our own goodwill rather briefly and modestly. Given that this letter is asking the patron to undertake a favour, an appeal to the patron not to get annoyed with the request seemed prudent. To the right high and mighty prince and right especial lord Duke Ædward do we recommend ourselves to your good lordship, beseeching your lordship that you take not to displeasure though we write you as we here say: The salutation as prince and lord is the appropriate one for a Duke as used in period, having been modelled on John Paston's 1472 letter to the Duke of Norfolk: To the right high and mighty prince and my right good and gracious lord, my lord the Duke of Norfolk It also follows the important rule to repeat titles and positive adjectives to sufficiently demonstrate the honour and glory of the recipient. The Body of the Text: narration and petitionThe next section continues from the salutation, reminding the recipient of the connection between them and the writer. This is an important point when such communications may be few and far between, and actual physical meetings rare. In 1472, John Paston attempted to jog the Duke of Norfolk's memory regarding an encounter with his brother and certain matters that had arisen out of that: Mekly besechyth your hyghness your poore and trew contynuall seruaunt and oratour John Paston the yonger that it myght please your good grace to call on-to your most discret and notabyll remembrance that lateward, at the costys and charge of my brodyr John Paston, knyght, whyche most entendith to do that myght please your hyghness, the ryght nobyll lord the Bysshopp of Wynchester entretyd so and compouned wyth your lordshepp that it liekyd the same to be so good and gracyous lord to my seyd brodyr that….

My letter attempts to gently remind Duke Ædward that we had discussed with him our petition to King Stephen Aldred for a letter patent granting us a licence to crenellate our house, the Hermitage. That we meekly beseecheth your highness your poor and true continual servants and oratours Bartholomew Baskin and katherine kerr that it might please your good grace to call on to your most discreet and notable remembrance that lateward we had entreated so and compounded with your lordship of certain letters patent, viz a licence to crenellate our great manor of the Hermitage in the Barony of Southron Gaard, in such manner whereof we had beseeched the late sovereign lord King Stephen Aldred for said licence. It then references the original wording of the letter patent, that I had based on a number of licenses still extant Then did we humbly beg to be granted walls of stone and lime, and that we and our heirs may hold it, thus fortified and crenellated, in perpetuity for the habitation of ourselves and the said heirs and assigns for ever as surely and lawfully as we can devise without any fine or fee to be paid for the said letters patent, licence, or grants by us as said beseechers. The comment about "without any fine or fee" comes from a petition to Edward IV in 1464, wherein John Paston asked for a letter patent to establish a large establishment for priests and poor folk: Please it yowre Highnes to graunte vn-to yowre humble seruaunt John Paston the older, squier, yowr gracious lettres patentz of licence to fownde, stabilysh, and endewe in the gret mancion of Castre be Mekyll Yermowth in Norffolk…of the said mancion for euer, with-owte eny fyne or fee to be payde for the sayd lettres patentz, licens, or grauntes be your sayd besecher or be the said pristes. The original licence to crenellate wording included a similar clause, though not quite so money-directed. Then comes a bit more grovelling and a not-so-subtle attempt to remind the recipient of the utility of the relationship and the consequences of failing to assist: In consideration of the service and pleasure that your Highness knows to you done by your humble servants of old, we beseech your abundant good grace, in the way of charity, that our plea may by your highness be put before our sovereign lord King Draco that he may in his abundant grace see us restored into the possession of the said manor according to the law and good conscience that we may not be said to live in adulterine fashion the which daily vexes and troubles us to our sorrow and shame there-of. That was partially based on John Paston's 1460 Petition to Henry VI To the Kyng ouyr souerayn lord Ples yowyr Hyghnes of yowyr abundant grace in consyderacion of the seruys and plesur that yowyr Hyghnes knowyth to yow don by William Paston, late on of yowyr jugys and old seruaunt to that nobyll prinse yowyr fadyr, to graunt on-to John Paston…. Bearing in mind that this letter was to be sent to the patron for the hoped-for action to be undertaken at 12th Night Coronation, it was necessary to consider that the change in sovereigns may already have taken place before the plea be made, and so an additional sentence was added to cover that possibility: And that if the sad reports we have of the poor health of our sovereign said lord be true then we pray you take our plea unto His Highness the Crown Prince Alfar that he may know of our travail. The actual body of the letter, or narratio, contains the important material and subject matter. It, however, tends to be reasonably brief and to the point, particularly if it includes a petition requesting assistance. The commentators on letter writing recognised many forms of petition that one might be required make; this example is a supplicating one (deprecatiua) wherein the power is vested in the hands of the recipient who can choose whether or not to grant the petition. This is possibly the most straightforward portion of writing in the whole thing, and contrasts markedly with the very flowery language of the recommended salutations and concluding clauses. The ClosingThe closing usually involves fervent wishes for the health and well-being of the recipient, with the invocation of God's help; in deference to the SCA attitude to religion, I have elided over this aspect in my letter. It is often a place where some form of positive affirmation is made towards the recipient, without reference to the actual business of the letter. The closing of my letter uses the form from John Paston's 1454 letter to the Earl of Oxford: Right wurchepfull and my right especiall lord, I besech Allmyghty God send you asmych joy and wurchep as euer had any of my lordes yowre aunceteres, and kepe you and all yowres. Wretyn at Norwich the iiij Sonday of Lent. Yowre seruaunte to his powre, John PastonMy letter was to a Duke, mentioning the current King and his successor, so the expressed wish involving the ancestors seemed very appropriate. In eliminating the reference to Almighty God, I could also have changed the final closing peroration, but left "his power" in as an ambiguity, as it could well refer to the Sovereign Lord cited. Right worshipful and right good lord, we would send you as much joy and worship as ever had any of our lords your ancestors, and wish you and all yours all good fortune. Written at the Hermitage on the feast day of St Katherine of Alexandria in the second term of the noble reign of King Draco. Your servants to his power, Bartholomew Baskin et katherine kerrThe feast day of St Katherine is November 25, which seemed an auspicious day to date the letter from, as well as allowing sufficient time for the couriers to get it to the patron before 12th Night. According to Mathewes, it was more common for the gentry and nobility to date their letters -- when dated at all -- to a feast day and to remain rather hazy about what calendrical year it was, instead typically using the regnal year.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||