|

|

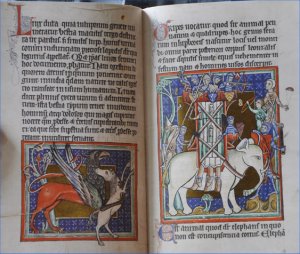

Bestiary Old Principality Bestiary [Main Printing & Manuscript Menu] Bestiaries have always fascinated me with their mix of the scientific and the fantastical. I had long planned to do one for Lochac, with the idea of setting up a Chinese whispers group to see what sort of description would come out the end if you told the starting person to describe a kangaroo, for example. I figured this was comparable to the garbled descriptions and misinterpretations of the period descriptions, where an elephant's ear are described as sticking out the side of its head "as a fishes fins doth", only to be depicted with actual fins stuck to it. When the topic came up for the Kingdom A&S Competition at 12th Night Coronation (AS45), that provided the impetus to get on with it, and thus a variety of approaches were tried. It was astonishing to see no fewer than 20 enties in the competition (we usually struggle to get three!); the judges were overwhelmed, so took the various absolutely glorious entries away as there was no way they could consider that many entries under the circumstances. Brilliant to see so many people and projects inspired by this topic. A Bestiary for the Old Principality of LochacThe model for my Old Principality Bestiary is that of MS Bodley 764, a 13th-century work produced in England. Richard Barber has translated the work from Latin and this translation, along with the life-size reproductions of the illustrations it includes, was my detailed guide.

According to Clark, vernacular bestiaries appeared very early on alongside Latin ones (pg iv). I decided that I would produce the text in formal, semi-forsooth English but with modern spelling rather than trying for something more appropriate for the period. The idea is that this would be comparable for the reader as if they were fluent in reading the original work in Latin, but still give a feeling of an older age. I have no idea what cover, if any, the original had, and have left mine blank. The first page prologue comes directly from MS 764; the remaining text is generally a combination of my material and quotes from the original masters, such as Physiologus, Pliny the Elder and Isidore of Seville. These early works are what are referred to as the First Family bestiaries, being the initial examples of the type. The likes of MS 764 and the famous 12th-Century Aberdeen Bestiary are termed Second Family; they heavily reference the earlier authors (sometimes even with actual citations!) and include other material. My original idea was to play a game of Chinese whispers with various odd local fauna and see what descriptions came out at the end. I tried an electronic version of this by providing helpful colleagues across the seas with uncaptioned photos of strange animals and asked them to describe what they thought it was like. Most of them had never heard or seen the creatures I nominated (I avoided the obvious like koalas or kiwis). My thanks to the AS50 group, particularly Isillin Teague, Johnnae, Eithni, Verena, Elewyiss and others who took up this challenge. My aim was to get something like that described by Diane Tillitson, which is delightful enough to quote at length: The result of the miscellany of sources, compiled in somewhat haphazard manner, and the fact that some had been translated from Greek, and lost a little in the translation, and the fact that many of the animals described were unknown to European readers, resulted in the most marvellous chaos and muddle in the text. Entries commonly start with an etymological derivation of the name of the animal, which is usually completely scrambled. The animals described include common domestic and wild animals of Europe, familiar to all, as well as exotic creatures such as the elephant or lion which might just have been seen by some living witnesses. Then there are animals which are most unlikely to have been familiar to anybody, so it is perhaps not surprising that they are ascribed some extraordinary habits. There are creatures which do not exist, although they became firmly entrenched in medieval animal mythology. There are confusions caused by mistranslation, so that the honey badger of Ethiopia somehow became an ant that digs for gold. Many happy hours can be spent trying to identify the origins of the animals in the bestiary.

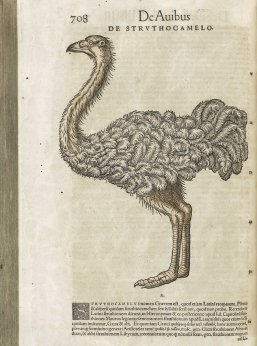

The ant section comes almost verbatim from MS 764, and the viper description from the Aberdeen Bestiary as I really liked that entry so decided to reproduce most of it as a salutary tale. Many of these bestiaries had long commentaries on the theological metaphors inherent in the beasts. The rest of the information is actually real, sourced from a wide range of natural history and zoological tomes, so this bestiary ended up far more accurate than its would-be contemporaries. Even the comment about pre-Raphaelite artist Rosetti calling wombats “the most beautiful of Gods creatures” is true! While fanciful descriptions and stylized drawing and painting often obscure the natural animals, both text and illustrations in fact can also reveal real-life details, forms and behaviors just below the surface. I think perhaps I should have introduced more fanciful notions to broaden out the descriptions. Some have been incorporated, though I suspect that the drop-bear story owes more to the koala than the Tasmanian Devil! The marzipol mole entry is a family joke – my son Peregrin has been a keen naturalist from a young age, and on finding out we were taking him to Australia, said he wanted to see a marzipol mole. It took us some time to figure out he meant marsupial (he’d seen the word written down, but hadn’t heard it said; he was 6 at the time). As for the artwork, it tends to follow the general pattern of “woefully distorted pictures of real creatures”, though I like to think most would be vaguely recognisable in outline. It has the “dazzling use of colour” of the original in very similar usage, although my palette is slightly different – clearly my scribe could not afford the profligate use of gold seen in MS 764. (I may go back over it and gild it once I get the hang of goldwork -- it does shine so beautifully.) The general image size and placements are comparable. Most of the images are loosely based on the original (eg the Tasmanian Devil was based on the depiction of the bear), and some are direct copies with slight modifications (eg the ants and the vipers). I kept the Dr Seussian trees and used some of the common decorative motifs from the borders and background panels. The illustrator based his drawing of an unknown animal on the written description or on other illustrations or carvings he had seen. Many manuscripts have peculiar animal pictures merely because of the lack of skill of the illustrator, who may have been the most artistic monk in the monastery, but no true artist. The Bodlean bestiary was produced on vellum, with the text written in littera textualis formata. I have very roughly matched the style of font, using Pia Frauss’s XiBerone font. This is a form of blackletter based on the 14th-century French lettering used by Gaston Phoebus in his Book of the Hunt. The text has been individually hand-kerned to give a very slight right ragged effect comparable to the original (ie so the text doesn’t line up perfectly to the right). The large capitals are from the Lombardic font family. I did consider doing the red/blue penwork around them, but couldn’t get a satisfactory flow to the practice lettering, so decided to leave well enough alone (perhaps a later addition). I did originally print the capitals but decided to overpaint them in goache for a better hand-done effect. I printed the work on a “goatskin parchment” which is a reasonably nice weight approximation for parchment. I have folded it but left it loose-bound as I want to include this in a major collection of works in a properly bound book at a later stage. What I failed to do was to take a scan of the inked in illustrations before I illuminated them. I intened to do that and insert the outline drawings into the material so that when you print the PDF out, you get a version you can colour in yourself. But first I have to get it back off the judges.... Crescent Isles BestiaryAs the Crescent Isles was slightly late to join the Kingdom of Lochac, it seemed appropriate that the Crescent Isles Bestiary should also adopt a late-period format, and thus this A&S entry was born. It is modelled on the 16th-century printed works of people like Conrad Gesner (or Konrad Gessner or variations between) and Edward Topsell. These gentlemen were foremost practitioners in collating all manner of zoological specimens and information, working text and illustrations into huge tomes that became highly popular works in the latter half of the 1500s and on through the 1600s.

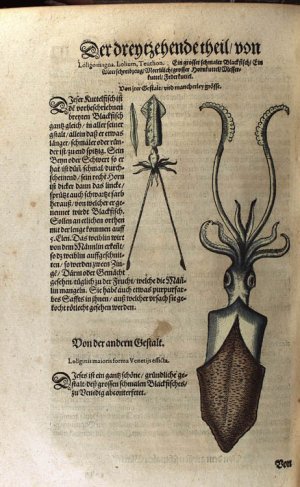

These works combined ancient and medieval knowledge from the early bestiaries with more modern natural history and actual observations, as well as myths, folklore and literature. As Topsell himself described in a long sub-title which I have cribbed: The History Of Certain Beasts…Describing at Large Their True and Lively Figure, their Several Natures, Conditions, Kinds, Virtues (both Natural and Medicinal), their Love and Hatred to Mankind, Interwoven with curious variety of Historical Narrations out of Papers, Philosophers, Physicians and Poets Gesner’s volumes were divided into various animal types, such as the Quadrupeds, Birds, Fish and other Marine Life, Serpents and even Fossils (the first work on such). I have used examples of most of these in my Crescent Isles Bestiary, but included Insects (a category Topsell later covered) to make up for the fact that we just don’t have any Serpents. Most of the internal layout in my bestiary has been based on Gesner’s Historiae Animalium, which consisted of four volumes published between 1551-1558; a final fifth volume followed in 1587. I also used ideas from Topsell’s History Of Four-Footed Beasts, which was a translation of Gesner’s work printed in 1607. The font is the JSL set developed by Geoffrey Shipbrook as a late-period printed font family, and the language has been rendered into a rough Elizabethanish to match the period in which it would have been produced. Crescent Isles Bestiary (11MB PDF): double-sided A4 printout, 7 sheets folded to 28 pages I grew rather fond of Gesner when I found that he was willing to be critical of dubious observations and beliefs. He noted that the hydra, although cited for centuries as a type of serpent had ears, tongues, noses and faces which were “inconsistent with the nature of serpents". Of course, this didn’t stop him noting down folklore, fancies and second-hand stories. It seemed somehow appropriate to use the introduction from Marco Polo’s Travels as the frontispiece, dealing as it does with the factual observation of things. Many of the general section introductions and most of the fish section have been adapted from Harrison’s 1587 Description of England. He, too, had a tendency towards caution in some of his descriptions. In describing Gesner’s approach, the King’s College exhibition curator noted that Gesner included: …information on the names of the animal in classical and modern languages, its geographical distribution, its behaviour and appearance, its internal and external features, the diseases that it suffers from and its uses, including its uses as food or medicine, as well as references to the animal in literature and folklore. While each section contains quotations from classical and medieval authors, there are also many observations provided by Gesner’s extensive network of correspondents from across Europe.

I followed those general principles. As with the Old Principality Bestiary, I used some descriptions sourced from people who had been sent a picture of the animal, without having any idea of what it was. Other information came from modern sources, such as the Department of Conservation, the Te Ara Encyclopaedia, Te Papa and suchlike. I also included references to traditional Classical sources such as Pliny and Isidore of Seville, though these were rather rare on the ground for New Zealand animals….

The main difference in the printed works on animals compared to the older bestiaries was in the quality of the woodcuts which, for the first time, depicted animals naturalistically such that most are readily recognisable to a modern reader. This was further improved in some volumes by hand-colouring in a naturalistic fashion. Gessner hired masters of woodcutting to make lavish illustrations for his book. Whenever possible, Gessner had them work from actual specimens. But Gessner’s artists couldn’t go to the Arctic or to Africa, so they still had to rely on second-hand information for exotic species. Gessner’s masterpiece is a transitional mix of the modern and the mythical. I didn’t have a local master woodcut person available to me, so most of the native animals illustrations consist of my pen and ink drawings based on Gesner’s woodcuts of comparable animals (or directly, in the case of the hedgehog). In an homage, of sorts, to the common period practice of nicking other people’s illustrations, I have used Gesner’s own ammonite illustration from 1565 (the first such ever printed) – the central depiction is almost identical to the actual specimen I describe, which can be seen in the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. The fish section has a collage of such “borrowings”. To finish, another favourite quote from Gesner: But if everyone publishes his observations for the public good, it is to be hoped that from them all one day one perfect work may be achieved . . . but this, I feel, will not be realized in our century. Probably not in our century either…. A Beastie Broadside – introducing the Colossal SquidOdd beasts have always intrigued humanity, and the development of printing allowed reports of the strange and marvellous to spread far and wide.

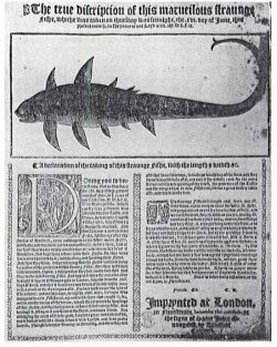

In the late 1560s, French naturalists Guillaume Rondelet wote the Libri de Piscibus Marinis on the natural history of fishes, describing some strange but recognisable characteristics, such as a fish that shone at night “like a star”. During the latter half of the 1500s, Swiss philosopher Conrad Gesner published a number of descriptive volumes of natural history covering quadrupeds, birds, fishes, insects and snakes, accompanied by woodcuts. Unlike the multi-volume tomes of the serious naturalists, broadsheet reports offered a quick inexpensive way of keeping up with the news, whether the landing of a Rare or Rather Most Monstrous Fishe taken on the East Coast of Holland in 1566 (identified as a cuttlefish) or the 1569 True Discripcion of [a] Marueilous Straunge Fishe (now recognised as a thresher shark). Some of these broadsheets were true fore-runners of the newspaper article, with cogent reports covering most of the facts – or rather, what were thought to be facts at the time. Others were stories that were turned into genuine broadsides with fishy tales transformed into lyrics supported by popular songs of the day (Lilly, pg 299). Shapiro notes that: by the late sixteenth century broadside "news" was beginning to be characterized by the conventions for establishing "fact" or "matters of fact"....There was an emphasis on identifying the precise time and place of the event and on providing proof by credible witnesses (pg 88) Thomas Colwell was a particularly enthusiastic London publisher of “strange but true” broadsheets, with a number credited to him covering sightings of sharks, killer whales and other oddities of the deep. He mentioned who had caught what, whereabouts and what happened afterwards, often emphasising the involvement of respectable people and many witnesses to bolster the legitimacy of the story.

I have used Colwell’s 1569 broadsheet as the basis for a beast report of my own – The true Discripcion of this Marueilous Straunge Collossus of the Seas. This broadside concerns the capture and eventual dissection of a collosal squid, undertaken by Dr Steve O’Shea and others at Te Papa Tongarewa The Museum of New Zealand in 2008. The text, although Elizabethan in spelling, usage and style, reasonably accurately reflects the events from the hauling up of the squid by longline fishermen in Antarctic waters through to the physical description that resulted from the examination. National Geographic coverage provided some of the more juicy details (such as the taste of colossal squid).

The illustration is based on the diagram on the Squid Fact Sheet, modified to reflect a woodcut style of the type used by Gessner to illustrate his own cephalopodic entries. I can see from the typography and layout that the original was printed on a larger sheet than the A4 that I have chosen to use; however the smaller size was more practical in terms of production (I don’t have ready access to an A3 printer) and distribution (I plan to use it as an example of how to go about producing period-style materials for an A&S class). As always, I am indebted to Geoffrey Shipbrook for his handy period font set (JSL Ancient, JSL Blackletter). The text of Colwell’s 1569 broadsheetThe true discripcion of this marueilous straugne Fishe whiche was taken on Thursday was sennight, the xvj. day of June, this present month,, in the yeare of our Lord God, M.D. lxix. A declaration of the taking of this straunge Fishe, with the length and bredth, &c. Dooing you to vnderstande that on Thursdaye, the xvj. daye of this present month of June, in the yeare of our Lord God M.D.lxix. this sztraunge fishe was taken betweene Callis and Douer, by certayne English fissher-men whych were a fyshynge for mackrell. And this staunge and merueylous fyshe, folowynge after the scooles of mackrell, came rushinge in to the fisher-mens netts, and brake and tore their nettes marueilouslit, in such sorte, that at the fyrst they weare muche amased thereat, and marueiled what is should bee that kept suche a sturr with their netts, for they were verie much harmed by it with breking and spoyling their netts. And then they. seing and perceiuyng that the netts wold not serue, by reason of the greatness of this struang fish, then they with such instruements, ingins, and thinges that they had, made such shift that they tooke this straung fishe. And vppon Fridaye, the morowe after, brought it vpp to Billyngesgate in London, whyche wa the xvij. daye of June, and ther it was eene and vewid of manie, which marueiled much at the straungnes of it; for here hath neuer the lyke of it ben seene : and on Saterdaye, beiing the xviij. daye, sertayne fishe-mongers in new Fishstreat agreeid with them that caught it, for and in consideracion of the harme whych they receiued by spoylinge of ther netts, and for their paines, to haue this straunge fishe. And hauinge it, did open it and flaied of the skinn, and saued it hole. And, aiudging the meat of it to be good, broyled a peece andtasted of hit, and it looked whit like veale when it was broiled, and was good and saueries (though sumwhat straunge) in the eating, and then they sold of it that same Satedaye to suche as would buy of the same, and they themselues did bake of it, and eate it for daintie; and for the more sertaintie and opening of the truth, the good men of the Castle and Kinges head in new Fishstreat did bui a great deale and bakte of it, and this is moste true. The straunge fshe is in length xvij. foote amd iij. foote broad, and in compas about the bodie vj. foote ; and is round snowted, short headdid, hauing iij. ranckes of teeth on eyther iawe, maruaylous sharpe and very short, ij. eyes growing neare his shout, and as big as a horses eyes, and his hart as big as an oes hart, and likesyse his liuer and lightes bige as an oxes ; but all the garbidge that was in hys bellie besides would haue gone into a felt hat. Also ix. finns, and ij. of the formost bee iij. quarters of a yeard longe from the body, and a verie bog one on the fore parte of his backe, blackish on the backe, and a litle whitishe on the belly, a slender tayle, and had but one bone, and that was a great rydge-bone, runninge a-longe his backe from the head vnto the tayle, and had great force in his tayle when he was in the waters. Also it hath v. gills of eache side of the head, shoing white. Ther is no proper name for it that I knowe, but that sertayne men of Captayne Haukinses doth call it a sharke. And it is to bee seene in London, at the Red Lyon in Fletestreete, Finish, quod C.R. Imprynted at london, in Fleetstreate, beneathe the Conduit, at the signe of Saint John Euangelist, by Thomas Colwell. The text of the Collosal Squid BroadsideThe true discripcion of this marueilous straugne Collossus of the Seas, whiche was reueal’d from May daie in the yeare of our Societie XLIII. A declaration of the obseruacion of this straunge Beaste, with the length &c. This straunge beaste was taken within the waters of the Greate Whyte Southron londe by some cer- tayne fissher- men of the Crescaunt Ises ship Sans Aspiring whych were a fyshynge for toothefysh on a longlyne. And this staunge and merueylous beaste came rushinge in attached to a toothefyshe and was taen into the fisher-mens netts. And then they seing and perceiuyng that the netts wold not serue, by reason of the greatnesse of this struang fish, then they with such instruements, ingins, and thinges that they had, made such shift that they tooke this straung fishe. When cawt the beaste was brighte redd. And for a yeare or mor the said beaste was kept within the grippe of ice vntill learned men could come vnto it and then it was eene and vewid of manie, which marueiled much at the straungnes of it; for here hath neuer the lyke of it ben seene. And hauinge it, men from manie countries did open it and flaied of the skinn, and looked vpon it minutly & took its measure such that all might knowe of it. The beast — term’d by the natturall philosophaurs the Collossus of the Seas and named fore its midclaw — is in length xiv. Foote tho much beshortened in Death & such are thot to grow the largest of any animale sans a spyne. It is souter than its Giante cuz as it masses some thousand pounds ; and it hath a beak like a papingo but of muche greater siz. It was sayed that in daies of olde a Giant creature of this type washed vppon the shores of Dartown and when payced came to lv. foote but some saie nay. And of its eyen were twa near vnto the size of a mans hedde, of alle animals the largest, facing frowards and rang’d all about with glowyng pointes such as might lyght the Stygian depths from whence this beast emerg’d. And of ten limbs it ressembles nigh the octopdes but with geat rings of suckers and a score of swiueling hookes on each of the long arms and tripartie hookes with claws on the small to club and scar mightilie aginste its enemie the greate sperm whale which feeds vpon this beaste (as is knowne from the beaks found therein the stomach of the greate fish). And, aiudging the meat of it to be good, they broyled a peece and tasted of hit, and it looked whit like veale when it was broiled, and was saueries (though sumwhat straunge) in the eating it being ammoniackal and toughe of mussel. Ane man who ate of him sayeth it taysted bitter so that the fysshe-mongers lost hearte. And it is to bee seene in Dartown, at Our Playce wherein is kept the treassours of the Crescent Isles. Finis, quod k. k. Imprynted at the Hermitage, in ye Crescaunt Isles by katherine kerr.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||