|

|

Embroidery[Heraldic Chair Seat] [Velvet Sleeves (period favour)] [Elizabethan/Kiwi Coif] [Baronial Bayeaux Tapestry] [Table Runner] [Favour] [Cushions] [Book Covers] [Sleeve Inserts]I never thought of myself as an embroidery person until I started to try small projects, usually commercial kits which supplied everything in a needlework-for-dummies format. I've progressed a bit since then, and will cheerfully tackle most things, though French knots have always eluded me! I think blackwork suits me best, in terms of my persona and the nature of the result. Here is a selection of the various things I've tried over the years. Heraldic Chair SeatWhen my lord and I stepped down as Baron and Baroness of Southron Gaard in February ASXLIII, we finished our final court and then picked up our court chairs and carried them away, to sit at the back of the populace. As soon as I sat down, the ancient canvas gave way -- clearly an omen! So I needed to repair it...and that led me to consider embroidering an heraldic item to attach to the new canvas. I had been thinking about doing an heraldic cushion, inspired by the long list of heraldic applications provided by Coblaith Muimnech on the AS50 list. Here was a good reason to undertake a comparable project. As part of my early, rather vague cushion research, I'd looked at various depictions of heraldic embroidery. I particularly liked one in Innes' Scots Heraldry, complete with shields and animals and entwining plants. I wasn't particularly confident about drawing up my own pattern for such a piece, so I went on the hunt for a suitable chart. Nothing really grabbed me, and time was passing -- I wanted the seat done for November Crown. I idly flicked through Debby Robinson's Medieval Needlepoint book (Collins and Brown, 1992) hoping for inspiration. I'd liked many of the designs (having done one years ago for my son Peregrine) and decided that I could put together something suitable based on one of the patterns. The intertwining oak-leaves were taken from the Livre des Merveilles, a book of hours from the early 1400s. At this point I knew that I wasn't going to be able to claim any kind of period approach, but the oak leaves appealed as it's one symbol I've used a lot in embroidery and elsewhere for my children, growth and strength.

I decided that the centre of the cushion would be a KK cipher. Mary Queen of Scots is well-known for the use of ciphers made out of letters, and the symmetry of the KK mirroring each other meant I ended up with a central lozenge -- a conveniently appropriate shape for displaying the arms of a woman. Somewhere in the translation between the Robinson design and my cipher, I lost the symmetry I had intended in the leaf areas, with the left size ending up distinctly wider than the right. I only noticed at a point far too late to do anything reasonable about it, so bit the bullet and continued. As a result, the right side was based on the Robinson material, but more freeform, with elements taken from it rather than a pattern followed. I did try to get the same colour density on either side, but the right is a little light bacuse of its smaller surface area. The border was similarly made up as a means of using up all the small ends of tapestry wool left over, without any specific patterning. Final production left a lot to be desired in many respects -- never try sewing something in a hurry an hour before you have to leave for a major event.....Ah well, the piece went onto the canvas, the canvas fitted the seat, the seat functioned perfectly fine. There are some finishing touches that need doing -- sewing some cord or braid over the edges to hide them, a fringing along the front flap perhaps, maybe a matching band for the back support. I suspect, however, that it may well stay in this form for some time.... Velvet Sleeves (period favour)This was undertaken for the Kingdom A&S Competition at May Crown AS43, in Darton; the topic being Favour (period). I dithered a bit as to whether to put this in my garb section or my activities section -- the usage would suggest activitites, but the final focus was on the embroidery and that's the emptiest section so here it is. Whenever knights gathered for a meet, Each wanted first place in every test, To do well, if he could, and so measure Up to providing his lady's pleasure. They all treated her as their lover, They all carried her love-favor, Ring or sleeve or banner-flame And all had one war-cry: her name. Historical SettingToken or favours are a well-known part of the romance of chivalry. The lady hands her favour to her lord, representing her love; he wears it on the field of combat to be inspired and do honour to her name. But like so many things we "know" about the Middle Ages, there is both more and less to the concept of favours. Certainly there are literary and historical references to the use of love tokens and simple marks of favour. Chretien de Troyes mentions the use of tokens in the four Arthurian Romances she penned in the mid-12th century. In the story of Eric and Enide, at a tournament near Tenebroc: There were so many scarlet banners, kerchiefs, and sleeves, many blue ones and many white, bestowed as tokens of love. In Cliges, the Queen gives Alexander a white silk shirt, stitched in gold and silver, as a token of her favour; Soredamors, who worked on the shirt, included a strand of her hair alongside the gold thread. In Book 18, Chapter 9 of Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, the Fair Maid of Astolat, Elaine le Blank, was "so hot in her love that she besought Sir Launcelot to wear upon him at the jousts a token of hers". Lancelot was apparently oblivious to her subtext, treating the gift merely as a means of improving his disguise on the field: …by cause he had never fore that time borne no manner of token of no damosel, then he bethought him that he would bear one of her, that none of his blood thereby might know him. The token Elaine gave Lancelot was "a red sleeve…of scarlet, well embroidered with great pearls", and Lancelot wore it upon his helm in the jousts. On finding out about this, Queen Guenever was "nigh out her mind for wroth" at him for doing so, and was not reassured by Sir Bors' protests on behalf of Launcelot's emotional neutrality. Clearly she saw some deeper meaning in his actions (18/15). Sadly Elaine was later disabused of her girlish dream and died. Guenever wasn't the only Queen displeased by wearing of a favour - in The Story of Flamenca, the (un-named) king of France fastened a sleeve to the tip of his lance, whereupon: The queen gave no sign that she was displeased by this token, but she said to herself that, if she knew who had given it to the king, she would make her rue the favour she bestowed. Once again a knight, Archambaut, lord of Bourbon and the husband of the lady thought to have provided the sleeve, attempted to assuage the queen's wrath by saying that the token was worn only as a sign of "knightly duty" (Bradley). In The Treasury of the City of Ladies, Christine de Pisan mentions love tokens somewhat disapprovingly, noting that all men would plead for them as part of a seduction attempt. She does say that a lady could extend "prudent largesse" to a "deserving" gentleman, knight or squire of good courage who was not able to outfit himself. This largesse related to armour and other gifts to encourage "nobility and high standards in others" (Chapter 20, pg 115-116). The favour I have made clearly falls into the category of a love token along the lines of the sleeves, rings and belts mentioned in the romances - it going to my lord as a mark of love and respect - rather than a more emotionally neutral, though far more practical, item of largesse such as a horse or armour.

MaterialsMy lord's arms are gules and argent, and I chose to use these colours, as they matched well with various period descriptions of tokens, such as the Maid of Asolat's red sleeve with white pearls. Typically there wouldn't be a relationship between the sleeve colours, simply being an item of apparel, and the lord's arms, nor would there usually be any symbology involved, such as the initials or charges commonly found on SCA belt favours. Elaine's "red sleeve of scarlet" is not a tautological reference -- scarlet is a fine woollen broadcloth which was typically red (hence the name passed from the fabric to the colour over time). The story of the Lady of the Short Sleeves recounted in Perceval, also involves a red sleeve, though of a different fabric: [Tiebaut of Tintagel] had a piece of crimson samite taken from his chest and immediately cut into a long, wide sleeve. He then called his daughter. "Daughter," he said to her, "rise early tomorrow morning and go to your knight [Gawain] before he sets out. As a token of love, offer him this new sleeve, and he will carry it when he rides to the tournament." (pg 64) I had a look at the wool available, and none of it seemed to be quite right to pass for proper scarlet. I found some "natural silk" which was roughly the right texture for the silk twill approximation to unpatterned samite suggested by Þóra Sharptooth. It was an off-white, requiring a dye job. I bought the dye, discussed it with others more experienced than me, and both time and confidence shrank.…I decided to use red velvet instead. It's a fabric appropriate to my persona placement of mid-16th century Scotland, and not unfitting for such a project as this. The fine gold line was chosen against some thicker gold cording because of its sheen against the velvet, and its light weight relative to the velvet. The pearls are natural freshwater pearls and, while not exactly the "great pearls" mentioned in Le Morte d'Arthur, these sort of pearls were well known in Scotland during my period (and they look a lot better than the plastic beads I've used to date!). They proved somewhat difficult to deal with as their holes were very fine, even with the silk thread used to sew them. I almost had to resort to a two-stage wire pull and rethread technique, but fortunately Mistress Roheisa had a needle finer than my beading needle which could do the job.

The silver rose studs are ones I have had for a very long time and used on other garb; they very closely approximate the studs on the flat cap of the painting of an unknown girl (c 1569), attributed to the Master of the Countess of Warwick (Ribeiro and Cumming, Plate III). They are also a reference to my persona's connection to the Yorkist cause. The sleeve lining is the silk originally purchased for the project. It provides some body for the velvet outer. After washing it, I liked its texture even less, so I was pleased not to have it as the main fabric. Design and ExecutionWhen my lord began fighting some six years ago, I made him the standard SCA belt favour. The design for that was based on a book cover design in Elizabethan Needlework Accessories (Marshall, pg 47) and incorporated our charges in a heart-shaped twining pattern. It's sweet but a complete SCA fiction. I also have made a large wall banner with a variant of that design on. However, the basic underlying design of the embroidery has period precedents. Norris provides sketches of very similar patterns citing portraits by Moro of a Spanish lady (pg 580) and a late portrait of Robert Dudley (pg 534). While Norris is not generally considered the best of sources for costuming advice per se, the patterns he has drawn match in style sleeve decorations, guards and hose panes in portraits and pattern-books from the mid- to late 1500s in England and elsewhere. I sewed the velvet to a frame to stabilise it during the couching process as I didn't feel experienced enough to do it freehand, with this being the first complex couching project I've undertaken. I was told afterwards that period surface couching did not use metallic couching thread, as I had done, but haven't, as yet, found any suitably referenced discussion of this. The dressmaker's tracing paper I tacked on to couch over the design turned out to be a little robust when it came to pull it away from the embroidery, skewing it somewhat and requiring additional stitching to fix the shape. For the second sleeve I tried tissue paper and added a strip of interlining to stabilise the stitching. Sadly, that didn't seem to help particularly much, a result I put down to my general lack of couching capability and the relative fineness of the cord chosen. I cut away the interlining afterwards as it was not allowing the fabric to drape evenly. Once the gold line was couched, the pearls were added. The spray of flat fresh-water pearls is based on a drawing by Norris (pg 509) of a beadwork motif and helps fill the space in a suitable fashion. I hand-sewed the sleeves and lining using running stitch and backstitch, bagged it out in the usual fashion, turning up the sleeve ends after adjusting the fit. I had initially drafted three different sleeve patterns, based on various sleeves in Arnold. The original intent was to have a two-part sleeve with the upper seam open and pearls catching it down its length. However, I suspected that this was going to present problems in getting the two sides of the design to match across the seam, so I went with a single under-seam and an embroidered panel along the upper arm. I do know that narrow embroidered panels were a common feature of mid-15th century Scottish garb (reference lost in the mists of time).

I had intended to put ties on the sleeve head, but I wanted the sleeves to sit over the shoulder of the gown they were to attach to. Consequently, I ended up using rings instead. I wasn't sure about the correct finishing, as I hadn't used this approach before, so I sewed the rings on using red thread to take the stitching through to the right side and secure it; I then hid the red stitches showing in the lining with a cream silk thread overlay. Presentation"God keep you and grant you honour on this day. Please wear this sleeve that I give you as a token of my love." These lines from Parzival provided the inspiration for how to go about presenting the favour. I begged leave from Their Majesties to present the favour in Invocation Court where the fighters and consorts are presented to the Crown. I assured that Crown that "While I may hope that my lord will find inspiration in such an action, please be assured that such will see no Unseen Powers called upon to assist him, lest there be detriment to his honour". They were kind enough to grant my boon. It was a great venue for it. They Majesties rode in to Invocation Court, and those fighting and their consorts marched in, each behind a banner bearer. In the absence of our children, young Eric Braythwayte was kind enough to bear my and Bartholomew's standard. I chose to present the left sleeve, as it is the closest to the heart, a piece of symbolism familiar to the medieval mind. Andreas Capellanus, in talking of token rings, states that they should be worn on the little finger of the left hand, because the left hand is "kept freer from dishonesty and shameful contacts"!

Fixing the FavourI haven't found any indication that a lady's favour or token was ever worn on a belt, as per standard SCA usage. In Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival, Book 7 describes how Obilot, daughter of Duke Lippaut, gives a sleeve to Gawain who nails it to his shield! Given the work I had put into the sleeve, I wasn't in favour of that approach…. In the story of the 13th-century German tourneyer Ulrich von Lichtenstein, Sir Otte von Spengenberg was described as having tied around his helmet "a veil of an expensive kind". Sir Launcelot wore the Maid of Astolat's sleeve on his helm, though Le Morte d'Arthur is silent as to how it was affixed; that hasn't stopped romantics depicting it being tied (see accompanying). Getting closer to my own period, in 1520, at the Field of Cloth of Gold, the King of France and his partners " wore sleeves on their head pieces" (Russell, p.128). For purely practical reasons alone, I chose to follow Fox-Davies, where he discussed how a ribbon, handkerchief or sleeve was "twisted in and out or over and over the fillet joining the crest and helmet". He cites it as being "not unlikely that the wide hanging mouth of the sleeve might have been used for the lambrequin" (pg 304). My sleeve doesn't match that, however, as it follows the closer wrist closure of the mid-Elizabethan period of my persona. My lord's helm lacked a crest in this tournament, so I added a little extra historical resonance and made a long version of my new hose garters, with small heart-shaped studs, This provided a means whereby I could wrap the sleeve securely and attach it to my lord's helm without any concerns about it getting in the way of his vision (or even likelihood of being hit!). I added an inspirational phrase to the strip of leather - not honi soit qui mal y pense, but a bon mot my lord likes to use: …never stop dreaming for out of such fragile things come miracles When I secured the sleeve to his helm, I used the lines from Parzival and he replied in kind. I'm told that some watching grew misty-eyed. AfterwordThe sleeve and its documentation were presented for judging at the Crown Tourney A&S display. The judging focused on the actual sleeve construction and embroidery techniques, rather than on its use as a favour, which is where I was focused. It can be a problem where there are differing interpretations of a category - to me a sleeve is a sleeve, a glove is a glove, a ring is a ring and it is what is done with that item that turns it from a sleeve into a favour. C'est de guerre. So my poor couching was a problem - I must see if I can retro-fit more couching stitches in place, as the narrow thread I used needed that to prevent distortion. The thread may also have been a bit too thin to properly show off the design; a double thread would have given more impact. The other problem was quoting older sources as the practice - I should have matched the sleeve to the times (which would then have made them inappropriate for me to wear at all!). I know an educated lady of my time would be familiar with Morte d'Arthur and the other texts noted, despite them being a century or two earlier, as the romances were popular fare during Elizabethan times and often used as the basis for the highly pageantry focused tournaments and tilts of late period. I'll need to keep an eye out for references to the use of mid-1500 favours at such events - perhaps Elizabeth's renowned jealousy put the ladies off! Update: So, many years after this I was chatting to Mistress Marienna about A&S stuff and mentioned my take on this project being about the use of the sleeve as a favour, rather than as a display of embroidery, and she had some very thought-provoking comments (helped by being one of the original judges...). We'd been discussing my assertion that things did not have to be perfection to be period -- embroidery didn't have to be 36-count reversible; we just see the very very top-end preserved because it is the best. I have claimed from time to time to be the Laurel of the Mediocre, though others have objected to that, so perhaps Laurel of the Ordinary would be more accurate to the sense I mean. Anyway, Marienna countered this with the thought that someone making a sleeve intended to be a favour would be darned sure to put her very best effort in to make it perfection -- worthy of its ultimate use -- and hence the production quality would, in fact, be a major issue. Good point! More on this topic here. Elizabethan/Kiwi CoifThis coif started life as a practice piece for a set of sleeves that have long been in the planning. The original intent was to produce a set of gauze-covered blackwork sleeves based on the painting in the Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh, by John Bettes II, titled Unknown Girl (1587), as this would suit both my persona and embroidery interests. In looking at the type of patterns used on those sleeves and on other examples of Elizabethan blackwork, there is a clear corpus of work and design, with period pattern books drawing on contemporary sources of drawings of plants and animal. As Gostelow says (pg 31): …a study of early English blackwork embroidery is a veritable horticulturalist's delight

I intended to follow this practice, but decided to incorporate plants and animals unique to my modern country of residence, New Zealand. The herbal and floral books that provided designs to Elizabethan embroiderers included The New Herball (William Turner, 1568) and The Herball of General Historie of Plantes (John Gerard, 1597). I've used a number of Andrew Crowe's books and flip guides for the same purpose, taking patterns from the life-sized illustrations of appropriate plants and animals and also using the cross-stitch patterns by Parker for inspiration. I identified a range of New Zealand plants and animals similar to those used in Elizabethan blackwork, but readily identifiable as flora and fauna natuive to New Zealand. Many of the plant forms are similar in silhouette to the English forms used in Elizabethan blackwork: the manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) flower has a very similar shape to an heraldic rose, although its leaf shape is markedly different; the kowhai (Sophora microphylla) flower is almost exactly the shape of the Elizabethan peapod (Gostelow, pg 72), but doubled and mirrored to produce the appropriate flower form; its leaves are an exact match for the peapod leaves seen in a lady's jacket from the 1570s held by Maidstone Museum, Kent. Other plants represented on the coif are pohutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa), kaikomako (Pennantia corymbosa), whauwhaupaku/five finger (Pseudopanax arboreus) and kawakawa (Macropiper excelsum). The latter has a deliberately incomplete filling pattern as these leaves are usually full of insect holes - it was gratifying to have a botanically aware person not only recognise the leaf but understand why I have left the area blank! I have seen unfilled leaf patterns and incomplete ones in work-in-progress in period examples, but not one done quite in this fashion for this reason. There are four New Zealand native animals on the coif: a katipo spider (Latrodectus katipo), a giant weta (Deinacrida heteracantha), a Superb land snail (Powelliphanta superba), and a peripatus (Peripatoides). Spiders and snails are common elements in Elizabethan blackwork, and the weta and peripatus are intended to replace the comparable cricket and caterpillar seen in period pieces. As with Elizabethan usage, the peripatus and spider are larger than life; however, the snail and weta are only around one-third actual life size - any larger and they would have taken up a great deal of the available space!

As a dedicated anachronist I had been toying for some time with the idea of incorporating a set of modern scientific images in period embroidery styles, such as the DNA double helix or nuclear decay spirals. Close examination of a range of period examples convinced me that it would be possible to incorporate these motifs in a period-looking fashion. Such examples included the forepart strapwork on the 1573 George Gower portrait of Mary Cornwallis, the free-form spiralling shape of the scrolled foliage in George Gower's 1573 portrait of Lady Elizabeth Kitson, and the cross-barred strapwork of the Middleton double-frilled cape-collar. Aspects of these were combined to produce a stylized DNA helix, with its double spiral and four base pairings. The ends of the smaller individual spirals and the set of koru ferns are the same shape as those used on Mary Cornwallis' sleeves, and the free-form approach to the overall pattern is comparable to that in the Bettes painting.

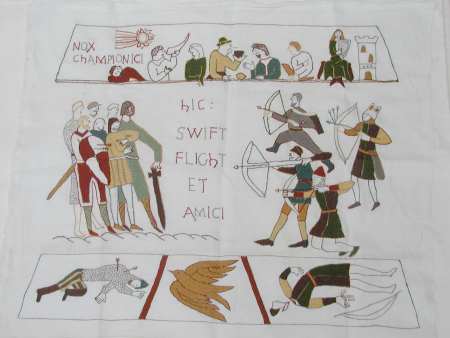

I've used predominately stem stitch and back stitch, with the main outlines in doubled thread to vary the weight of the major design elements. Gold thread and beads have been used to add highlights to some of the patterns, with couching, spangling and speckling approaches taken from the 1562 portrait of Lady Throckmorton. Filling stitches were taken predominantly from Wilkins and also from the 100 Blackwork Charts published by the Skinner Sisters; both sources base their material on examples from the V&A and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, amongst others. The whole produces a fairly open effect, but this is not uncommon in a number of the larger items still extant. I'm still working on getting it to sit right. Maybe I'll try out a matching forehead cloth in future to pin it to. And then there are those sleeves.... Update. Ask and ye shall receive! I tried asking some Very Knowledgeable People about my problem in getting the coif to sit on my head without sliding off. The amazing Attack Laurel lady, Mistress Isobel Gildingwater of Ditchingham, pointed the way with her helpful article on How to Wear an Elizbethan Coif and told me that I had my ties in the wrong place. I'd assumed that they tied under the chin (as in the photo above), but in fact you pull them tight to gather and sit at the nape of the neck. This sounds really counter-intuitive, but by god it works. I now have a coif that sits firmly and snugly on my head. The next problem was to deal with the pointy bit, which annoyed me no end. I'd tried faithfully following the instructions but couldn't seem to get it to sit right. Dame Yolande Kesteven told me to use small knife pleats, rather than a gathering stitch along the top seam, and to take those around the curve past the point where the seam ends. That works too. Huzzah! I now have a properly shaped coif that doesn't come off. Now what? Oh yes, those sleeves..... Baronial Bayeux Tapestry Project: Swift Flight and FriendsThe Seamsters Guild in Southron Gaard undertook to record important events or aspects of life in our Barony as part of the Baronial Bayeux Tapestry project. As co-founder of the Swift Flight Light Infantry Company, I chose to record the Company for posterity. We used linen and Medici wool in commercially available colours identified as reasonable approximations of the original colours, based on comments made by Mistress Siban, a Laurel in Early Period Embroidery.

The stitching primarily is the stem/outline and laid work of the original. I have used backstitch for some of the finer detailing (this was my first attempt at this type of embroidery, and it seemed to be the only way I could get the mail and facial details to work). According to Jan Messent (The Bayeux Tapestry Embroiderers' Story; Madeira, 1999), at least one of the original embroiderers used a non-standard stitch (chain stitch), so there is precedent for being slightly different. The main elements of the central panel are taken directly from the Bayeux Tapestry and adapted to provide a representation of members of Swift Flight and Friends (ie over a dozen of those who were involved in the Company and those who played with it at the start of mixed combat in this region are identifiable). "Nox championici" is bastardized Latin for "Night of Champions", referring to the entertainment event organized by Swift Flight for a number of years following Canterbury Faire. The three beads on the tower at top right are anachronistic, as no beading was used on the original, but are there to represent my three children. The lower panel also uses images taken directly from the Bayeux, although the archer to the right has had his string fingers chopped off as a direct reference to the threat against the archers of Agincourt. The tapestry has now been incorporated into a Baronial Hanging, so may actually see the light of day. Table Runner

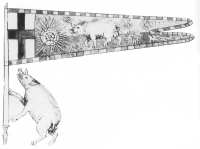

My table runner is based on a banner said to have been borne for Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. The motif of the white rose impaled on a sun in splendour reflects two badges identified with the House of York. A lot of my garb and gear has Yorkist motifs because of my persona's family's ties with the House of York (katherine kerr's grandfather was Francis Lovell, Richard III's Chamberlain and lifelong friend). Synchronicity strikes, as the sun in splendour is also the clan badge of the Kerrs.

This was put together in a hour or so flat in response to a table decoration competition announced for the Rose Feast at Canterbury Faire, from some spare cloth and ribbon. As Wars of the Roses, the theme was red and white, and those are my lord's colours, so that tied in nicely. The sewing is not as high quality as it could be, but it looks pretty good nonetheless. I made the runner long enough to stretch across the usual space our family takes up, or to span the width of a table, as required. The small metallic sun in splendour in the centre is actually part of a string of Christmas decorations, which proved to be an excellent, inexpensive way of getting a lot of suns. I've used ceramic white roses, from a set of bridal notions, and gold aglets as corner weights to help hold it flat. These have also come in handy for my belt. Favour

When my lord Batholomew Baskin took up heavy fighting, I figured he had better have a favour. This one is based on a design from Elizabethan Needlework Accessories by Sheila Marshall (Georgeson Publishing, 1998).The heart-shaped containment seemed particularly appropriate for the main element of a favour. The lion dormant gules is a charge which Bartholomew has used for a long time, the tower argent is mine. The thistles in the base of the tower's heart area represent the Scots connection, as katherine is a 16th-century Borderer. It's primarily a mix of satin stitch, chain stitch and backstitch. I like using whipped chain stitch in metallic threads to get a nice raised effect. There are also some silver rosebud beads, as a York reference. The sun in splendour at its base helps hold it down, and is a Kerr clan symbol as well as a Yorkist one. I got that particular one at a small notions shop somewhere in a back alley in Budapest. It looks a little weather-beaten at the moment as my lord has had it tied to his leather coat of jacks and it gets a reasonable pounding or grass stains each time he fights! I'm in the process of producing a large version which we'll use as a banner in lieu of my device being passed. That has twisted gold cord for the outer heart-shaped frame and the internal figures are generally of appliqued felt with gold thread. The upper leaves have been changed to oak leaves, in reference to Bartholomew being English. CushionsThe blue lion cushion, made for Bartholomew, was my first attempt at tent stitch. It came as a kit, designed by Julia Hickman, and I only modified it very slightly, mostly to add the BB initials. The lion is taken from the 14th-century Wilton Diptych. The red falcon cushion uses a design from Debby Robinson's Medieval Needlepoint (Collins and Brown, 1992). It was done for my son Peregrin, hence the subject and the gold P worked into the background.

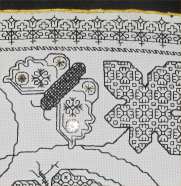

The blackwork cushion, which is one I use, was a kit, with some modifications from me. It represents my first foray into blackwork, which proved suitably inspiring that I've done other projects in blackwork (it's unusual for me to do anything twice).. Book CoversThe blackwork book cover was based on a sampler design produced by DMC. I've modified it to include some patterns I wanted to try out, as well as my name and tower symbol. It's been mounted on archival board with a black leather book cover to hold a clear file with any current entertainment material or other printed matter I need.

The cross-stitch comes from a Teresa Wentzler castle sampler kit. It was my first cross-stitch effort and nearly drove me mad with the many varying combinations of single strands of coloured thread. Took me around a year to complete. As with most kits, I modified it a tad, choosing not to add the alphabet edging and putting my name across the bottom. It's been mounted on archival board with green leather to serve as the holder for my music books. This makes it a bit unwieldy to put on a music stand, but it means I know where everything is. I am toying with pulling it apart and turning it into a box cover instead, as that might prove more useful.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||