|

|

Family PapersBaskin-Kerr and Consort Correspondence Kerr Papers: [Persona Story] I started this project for a Kingdom A&S Competition (May Crown, Darton, ASXXXIV): Patents of Nobility: papers that show noble descent to enter lists. Little did I know that it would become a minor obsession leading to no fewer than nine entries in the competition and an AS50 Depth Challenge covering all manner of papers, printed and manuscript.

The initial project covered the various documentations I researched in looking at just what would one use to prove a sufficiently noble identity to be allowed to participate in a tournament. As time passed, and my enthusiasm for family documents increased, I've added more and more material to this section. The original PON entries are now interspersed with other items, added in roughly chronological order, to keep the storyline more intelligible. When I first started researching this topic, I assumed that it would be easy to find period references to the presentation of patents as part of "signing-up" for the lists. After all, it is commonly stated that tournaments were restricted to nobility. That said, civic tournaments were commonly undertaken by non-enobled folk in various part of Europe (eg Italy, Flanders; Barber & Barker). Even the virtuous non-gentleman could take his place with the nobility after a suitably restrained beating for his presumption, as cited in Rene of Anjou's Tournament Book. As I worked through various specialised works on tournaments, I could find statements regarding the need to demonstrate one's nobility, but this was usually in terms of showing up with your horse and arms, displaying your crest, or providing proof that you or your ancestors were represented in tourney rolls of arms within the past 50 years (Barber & Barker pg 8, pg 186; Velde; Clephan, pg 130; Rottenkamp pg 98). The oft-cited Tiptoft Rules, devised by the Earl of Worcester in 1466, lists the precise manner in which jousts were to be held in England but does not appear to mandate the way in which entrants were to be deemed acceptable. Rene of Anjou's Tournament Book does note that "all may know which men are come of ancient nobility, by the way they bear arms and crests" and goes on to provide detailed instructions as to how such arms and crests should be made, borne and displayed by the would-be tourneyer, his horses and herald. These instructions included such exhortations to "princes, lords, barons, knights and squires", even captains, that they should: …have the heralds and pursuivants put up a long board attached to the wall in front of his lodgings, on which is painted his blazon, that is to say his crest and shield, and those of his company who will take part in the tourney, knights and squires alike. And he should have his banner displayed at a high window of the inn, hanging over the road. Some patents have some fairly anxious-sounding attempts to assert one's nobility: And I according to my said office and othe have been requyred by oon right worshipfull gentilman of the County of Derby called Richard Blackwall of Blackwall to enquire and search for the Armes of his Progenitors and Surname. Att whose request I the sayd Norrey King of Armes have serched in divers ancyent Books and Rolles pertayning to my said office And ther have found that of the same name hath been right Worshipful both of Authority and Armes as it apperyth in ye said Bookes of office Whereuppon I the said Norrey having respect and seyng ye Vertue and Substance of the said Richard Blackwall and his Possession sufficient to meyntayne his heirs ensuying at his desyre have devised to him and to his said heires for evermore thies Armes folowyng … On the Continent, such proofs were considered particularly important under the doctrine of seize quartiers (16 quarters), where nobility could be claimed if you could prove all 16 great-great-grandparents were entitled to bear arms (Robards, pg 122). That would require something a great deal more complex than a standard patent, which usually relates to a specific individual. The Germans, with their strongly codified approach to rank, were particularly keen on this. In Scotland, similar proofs have been applied, but generally at a lower level - Dr David Kinloch's birthbrief of 1597, for example, takes only the four grandparents into account, and Innes refers to this as the "proof of four branches" (pg195) A great deal of searching in both printed and online works has yet to reveal any indication that one would show an actual patent in order to enter a tournament. Seals and crests were readily transportable items, and are commonly cited as items produced to demonstrate one's arms and thus presumed nobility (Young, pg 46, Barker & Baker, pg 135; Wagner, pg 34). However, neither of those items are paper-based, and so do not fall within the terms of this A&S category although I may attempt their production at a later date As I sought further, I found more and more ways that people went about asserting their armigerous heritage, including various paper-based methods of demonstrating participation in previous tournaments as noted by Barber & Barker et al (cited above). This suggested a number of different approaches to the production of "papers that show noble descent to enter lists", and I have chosen to explore these as a series of separate but related entries in this A&S competition. All the individual entries relate to my persona story and have been developed with that in mind, representing the various papers that could have been presented in such circumstances:

Most of the documents have been drafted on paper, of a type comparable to that used throughout the 16th century, being a high-rag content paper and with a textured, rather than glazed surface (Leedham-Green). The most readily available modern approximation is watercolour paper of a reasonable weight (180gsm) and of archival quality. The other material used is parchmentine, a vegetable alternative to parchment/vellum that, these days, is more readily available and affordable than true vellum. This was recommended to me by Mistress Roheisa le Sarjent (Laurel in C&I) as a suitable approximation. The paints used are goache, generally recommended as suitable modern equivalents capable of producing a period-looking result in illuminations and illustrations. The ink is a plain black initially delivered via calligraphy fountain pen and, as I progressed, vai various dib pens with different nibs depending on the hand I was using. While I am experienced in producing period content, this project encouraged me to develop a range of handwriting and even some basic calligraphy, illumination and gilding. I have constructed a suitable coffer to hold these items -- a cardboard set of drawers from a local stationery outfit, covered in thin leather with green taffeta drawer fronts and metal handles precariously attached on the side. I lug it along to events to encourage people to rummage through the papers, printing and smaller A&S projects. The documentation is separate in a number of large clear files. Oddly enough, the historic Kerr family papers were sent in a coffer to Edinburgh Castle for safe-keeping during the castle's seige, where a demarcation dispute as to who would hold them saw them lost….

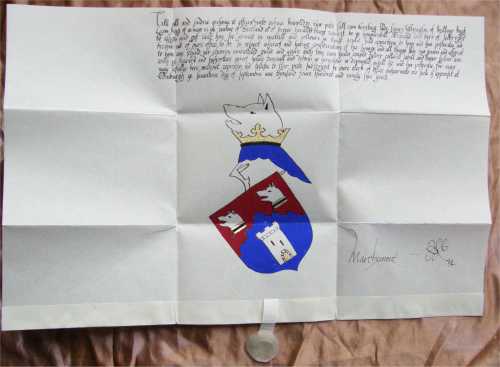

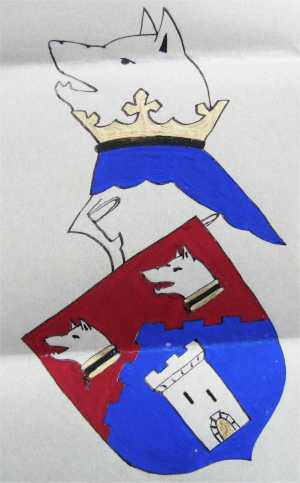

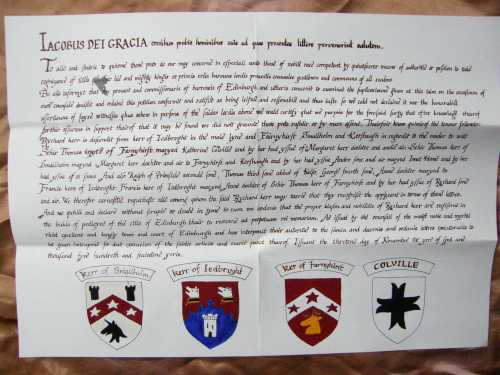

Francis Kerr: Patent of ArmsThe StoryIn November 1488 my grandfather, Francis Lovel, came to Scotland on a safe conduct, bearing messages from Margaret of Burgundy to James IV. He chose to stay, taking up a new identity and new life in Scotland following the fall of the House of York, marrying Anne Kerr, of the Ferniehirst Kerrs. Service with James IV during the latter's campaign against the Lord of the Isles and his brief invasion of England in support of Richard Duke of York (called by some Perkin Warbeck) saw Francis granted Scottish arms and a holding under the name Francis Kerr. The patent issued by the Lyon King of Arms was kept in a locked coffer. Although he adopted new arms as part of his new identity, Francis used his original Lovel family crest of a crowned dog's head.The BackgroundFrom the middle of the fifteenth century, there was significant growth in Scotland's peerage (Glozier, pg 18), with soldiers, statesmen and the heads of powerful landed families elevated to the peerage. Such elevations were recognised with Letters Patent, usually issued by the formal heraldic authorities such as the Lyon King of Arms. Often such recognition was accompanied with a grant of lands too, as noted in the Buke of the Order of Knichthede by Sir Gilbert Hay published in the late 15th century …the ordre of knychthede is sa hye yat wuhen a knig makis a knycht he ulde mak him lord and gouevnour of grete landis and contreis efter his worthines… In 16th-century Scotland, untitled gentry were considered to be noble in every sense of the word and such status was strongly upheld. It is estimated that as many as one person in 43 in early-modern Scotland had either a territorial designation or was closely related to someone who did (Glozier, pg 17), and this was regarded as grounds for nobility. Thus you could be noble without being knighted; furthermore your knighthood didn't have to come from the King (Stevenson; 2006; pg 62). James IV was known to raise non-nobles in his service to knighthood. Thomas Todd, who served as his royal messenger, was rewarded in such a manner for that (Stevenson pg 16). Generally it involved some form of military service and was related in some way to land holding (ie either a person with large holdings was ennobled; or given land on being ennobled). Land was typically mentioned as part of a title in Letters Patent. It should be noted that much of what is now recorded as Lyon Court functioning, with very strong control and definitive rules over Scottish heraldry, dates back to a 1672 Act of Parliament, although the named position itself was established by Robert the Bruce in 1318 (Velde). Thus one has to be very cautious in applying relatively modern ideas of Scottish heraldry in a period context. Even a standard reference such as Innes should be regarded with caution in attempting to extrapolate later restrictions into period times, when heraldry was much less codified. Given the valuable nature of patents, and the difficulty of transporting them with their often-fine artwork and heavy seals, it is understandable why the presentation of patents to a lists officer is not recorded in period documentation of tournaments. They were highly regarded and it was not uncommon for special small chests to be made to house and protect them. The OutcomeAlthough there are good grounds for questioning the premise of this A&S category, I have produced Letters Patent as the first in this collection of period identity papers. That is, a formal document issued by an heraldic authority under royal assent, comparable to the SCA patent of arms scroll, showing elevation to noble status. The two Scottish examples I have been able to source come from 1566-67, some 70 years after the date that Francis Kerr's patent was allegedly awarded. I found this rather surprising given how important patents were presumed to be, but in fact the Scottish heraldic authority Balfour Paul said of the 1567 Balfour patent that it was one of the earliest he knew of (pg 206). Bearing that in mind, having both reproductions of the actual patents as well as transcriptions of the Scots wording seemed rather fortuitous (sources: Innes, Heraldry Scotland, Littledate). So I modelled Francis Kerr's patent of 1496 on that of Sir James Balfour of Pittendreich of 1566 and on the 1567 patent of John Maxwell of Herries. Both these patents were matriculated by Robert Forman, Lyon King of Arms at the time.

The 1566/67 Scots patents are simple in style and decoration, with Balfour Paul noting that of the old Scottish patents "none that I know present any points of artistic excellence"! That suited me as this is the first hand-written calligraphy, illumination and gilding I have attempted. Patents dating back as early as the late 1400s were issued in English, rather than Latin, so having a version in Scots seems equally reasonable (cf Richard Blackwall's patent issued by Christofer Norrey King of Arms in 1494, quoted in the introduction).

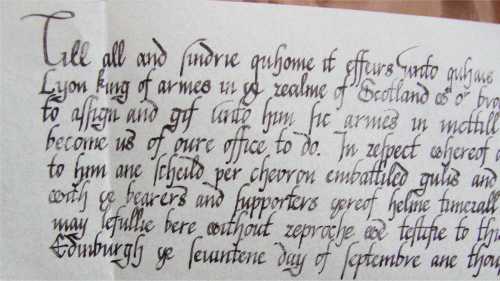

Innes provides a fairly poor reproduction of Balfour's patent (Plate XXV), but it is (just) clear enough to be able to cross-check the original Scots text against the transcription. A slightly better reproduction of the Maxwell patent allowed a closer look at the text as well as letter formation. Francis Kerr's patent is largely based on the Balfour text; I have carefully compared the transcription with the original and made adjustments where the former departs from the latter, most notably with regard to punctuation and capitalisation which appears to have been regularised in the transcription. Till all and sindrie quhome it effeirs, unto quhais knawledge thir pnts sall cum greting In God evirlasting, we, Schir Robert Forman of Luthrie, Knyt, Lyoun King of Armes, In ye realme of Scotland, wt our brother heralds being requirit be the honourabill Schir James Balfour of Pittendreich, knyt, to assign and gif unto him sic armes in metaill and colloure as maist deulie suld appertene to him and his posterite as become us of our office: In respect whereof, and having consideration of his lynage and all things, We has given and assignit to hym ane scheild sylver, ane chevron sabill, ane selch head in the centrepart thereof, with ane cinquefoil gules betwixt the outher parts of the same, with the bearers and supporters thereof, helme timerall and detoun as hereunder is depainted, quhilk he and his posterite for ever may lefullie bere without reproche for the causs foresaid, we testifie to thir pnts subscryvit be oure clerk of office quhairunto our seile is appensit at Edinburgh, the sixth day of Februar ane thousand five hundret three score six yeirs

I made a number of other changes after due consideration and considerable research: Patents in Scotland typically came with a land holding, so I have taken the liberty of giving Francis Kerr the holding of Jedburgh (Iedbrvght). This village is close to the Hermitage fortress and was, in fact, a holding of the Kerr clan three generations down from Francis (SirAndrew Kerr, of the Ferniehirst main line, was first lord of Iedbrvght; on the Kings and Nobilities Roll). Henry Thompson of Keillour was Lord Lyon from 1496 to 1512, responsible at the time this Patent was issued in 1496 (Stevenson). Note that Marchemont is a Scottish heraldic title. Some superscripts, abbreviations and special characters have been used in the original (eg wt for with; pnts for presents; the long s); these are well-recognised features of early modern handwriting and Scottish usage (Leedham-Green). Close examination of the script suggested that a standard secretary hand/bastard script would be suitable. I had a comparable electronic font: Winwenzlaw, a Bohemian bastarda from the 15th century. I used this to lay the text out to the correct size as a gloss from which to work, making necessary adjustments to more closely match the lettering of the original and typical Scottish handwriting formats (Scottish Handwriting.com). This included using three variants for r, the thorn for th, the Scottish w and the capitals which differed from the bastarda script.

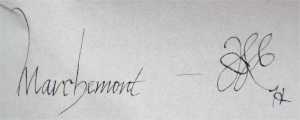

Several weeks of pen-practice went into developing a reasonably consistent hand. While I was closely following Forman's style and approach, I did not feel the need to match it precisely, as the patent was to have been issued by a different herald. One of the things I deliberately changed was the monogram at the end. It would not be correct to use the Marchemont monogram associated with Forman, so I used a different one, albeit one documentably period - in this case, it is the monogram used by Richard, Duke of York aka Perkin Warbeck (Wroe, Plate 6). Given his appearance in my persona story, that borrowing was particularly appealing.

The arms (mine as registered with the SCA College of Heralds) are depicted as in the older armorial rolls (eg Scots Roll, Gelre); this seemed more suitable than the late-period look of the Balfour/Maxwell patents with their scrollwork and laurel wreath (especially seeing the latter's SCA usage). Balfour Paul notes that the most common shield shape used in Scotland in the 16th century was "a simple square-shaped shield with a rounded base" - the traditional plain "heater" (pg 23). According to Balfour Paul and others, matching the colours of the arms to the livery - and by implication to the mantling - was not common practice in Scotland until very late period (pg 30). I have used a Gelre example of a blue cap/mantling (blue was one of Lovel's livery colours, and a blue cap of maintenance, in later Scottish heraldic usage, denoted a baron who had lost his lands). The crest is completed with a crowned cur's head, as per Lovel. Innes doesn't mention the type of material used for the patent, but I would assume from other examples that it would have been likely to be vellum. In this case I have used parchmentine as a suitable alternative that was available and affordable for this project, the first such I have attempted. Innes does note that patents were typically 19 inches x 24 inches (480 x 610 ml). I have based the size of this patent roughly on that, with the parchmentine being 500 x 700 ml and the proportions of the folded sections in the Balfour example used. The Maxwell patent is a different shape again, so some variation in this is clearly acceptable. I didn't have any ready means of producing a suitably decorated sized seal for this document. I've got a temporary one in there made from wax stamped with a large French coin. At some stage I will replace it with something more suitable. A Drawing of Margeurite Tydder

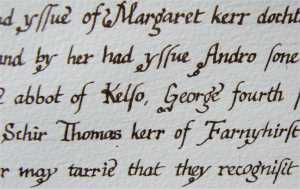

In the summer of 1503 my grandfather took my father to Berwick-on-Tweed -- where bears and dogs were let loose to sport together in the streets of the town -- to watch the progress of Marguerite Tydder, first daughter of Henry Tydder and Elizabeth Plantagenet, north to meet her new husband, James, the fourth King of that name. Father sketched the Queen who, at 13 years, was of his age. William Dunbar celebrated the arrival of the southerner with many poems; Now Fayre, Fayrest of Every Fayre declared: Sweet lusty lusum lady clere, She had bad luck from the start -- a few days after Father made this drawing, there was a stable fire wherein she lost her horses and her riding gear. A tournament was held in a meadow outside Edingburgh and it rained; many were the worse for drink. The English King's Printer Richard Grafton wrote poorly of the encounter stating: Then this lady was taken to the town of Edinburgh, and there the day after King James IV in the presence of all his nobility married the said princess, and feasted the English lords, and showed them jousts and other pastimes, very honourably, after the fashion of this rude country. When all things were done and finished according to their commission the Earl of Surrey with all the English lords and ladies returned to their country, giving more praise to the manhood than to the good manner and nature of Scotland. Worst of all, after the death of the King at Flodden she went on to marry Archibald Douglas, vith Earl of Angus, to the great doler of the country. The drawing, done in charcoal, is based on a sketch of Marguerite d'Angleterre from the Recueil d'Arras, a collection of pencil and charcoal sketches from the mid-1500s. Richard Kerr: BirthbriefThe StoryIn 1518, my father, Richard Kerr, went to serve in the Garde Ecossais of Francis I, the personal bodyguard of the French King. He took with him a birthbrief to identify his station as a member of the Scottish nobility, many of whom served in the Garde. This identity paper provided support for his claim to be able to participate in the tournaments at the Field of the Cloth of Gold a few years later.

The birthbrief functioned in a fashion comparable to a passport in that it was a form of identification paper which demonstrated the noble descent and right to arms of the bearer. It could be issued by heraldic, royal or municipal authorities, and was primarily designed to assist those travelling in foreign parts, such as an individual venturing forth to tourney or to take up an overseas role of some sort such as a merchant. Glozier says birthbrieves were a certification of nobility that accompanied Scots abroad throughout the Early Modern period verifying an individual's parentage and emphasizing their noble status (pg 18). They are text-based descriptions of parentage, sometimes dating back several generations to cover as many as the seize quartiers, or 16 great-great-grandparents considered important on the Continent to establish one's noble credentials. Innes does note that demonstrating descent from the four branches of grandparents was the normal proof of nobility in Scotland (Plate XL). Of the birthbrieves cited by Glozier, most belong to undesignated Scots (Scots without landed estate), who bear plain names. Glozier's work covers very late period through to the 1700s. The earliest mention of a birthbrief I can find dates to 1547, and the only physical example I have seen comes from 1597 (issued to Dr David Kinloch; Innes Plate XL).

The birthbrieve sets out "the descent, nobilitary status and all such matters relating to the social, feudal or tribal position of the petitioner as may seem useful at home or abroad" (Innes pg 193; Moody pg 85). Moody does mention its use in medieval times, noting that at that time a birthbrief could be obtained from the local town council or under the king's great seal and used as a form of passport in foreign cities. Innes mentions Municipal Propinquity Books maintained by cities such as Edinburgh and Aberdeen to record lineages in a suitably authoritative fashion (pg 115). These remained independent of the heraldic authorities until well past period (at least until the 18th century). In analysing a later birthbrief of 1669, Innes notes that municipal authorities were not necessarily as accurate as Lyon in recording lines of descent, and that they were "more modest" in their genealogical claims requiring proof. They were also significantly cheaper than the more florid versions produced by the Lyon Court, and hence possibly more popular with those of limited means or who had some irregularity in their lines that would not have passed scrutiny by Lyon. The OutcomeI haven't been able to find an example of a birthbrief text - the 1596 example in Innes is of too poor a quality to be able to read, even if it weren't handwritten in Latin, and enquiries to the Heraldry Society of Scotland have, sadly, yielded no response. Of all the identity papers presented here, this one has the most compromises due to a lack of readily available examples.

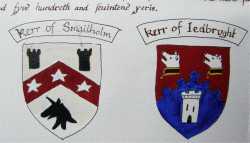

The Latin opening is taken from the standard openings used in the Parliamentary records of the reign of James IV; not enough of the Kinloch text could be discerned to accurately transcribe it. Given that Kinloch's text was provided under the seal of the Lord Lyon, and Richard Kerr's by a municipal authority, a simpler opening seemed reasonable. The genealogical description is based on Norroy's 1552 heraldic visitations of the north as an example of how the lineage of an individual may have been recorded and how this related to the family at large. The main example I have used is the entry for Davell (Ashmole MS. 834, part iii, folio 4b . Heralds' College MS. H. 19 , folio 15 .), as well as entries for Langdall and Bucton. In addition, I have used some of the text and style of birthbrief material mentioned in passing by Innes in his notes on the birthbrief of Walter Innes (Proceedings of the Society 1946-48, pg 114-118). That birthbrief was a municipal one issued in 1669, and the comments from and about the citation come from that text, modified for Scots usage of the early 1500s. Richard Kerr's birthbrief is a municipal one, issued by Edinburgh; his lineage as recorded is slightly irregular. Although it appears to record four quarters showing the arms, as per the Kinloch example, three of these follow through the female line, as Francis Kerr's true noble lineage cannot be cited for political reasons. Thus the emblazons include the arms for Ker of Farnyhirst, Kerr of Smailholm and Colville of Ochiltree in the mother's line, and Kerr of Iedbrvght in the male line.

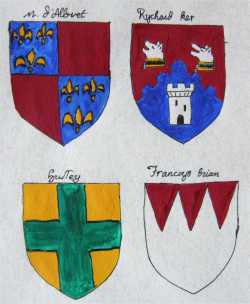

The Colville and Farnyhirst arms are period for those lines; the Iedbrvght Ker arms are my SCA-registered ones. The Smailholm arms are made up, using various related period charges - the sable unicorn head is associated with various Ker branches and the tower appears in the Colville crest, as well as in my own arms. I did that as I couldn't find a Smailholm device, although Kerrs held that holding for some time in the 1500s before it passed to the Pringles.

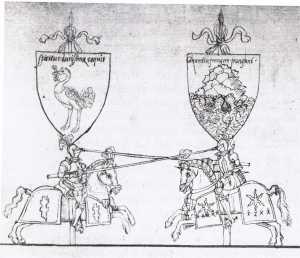

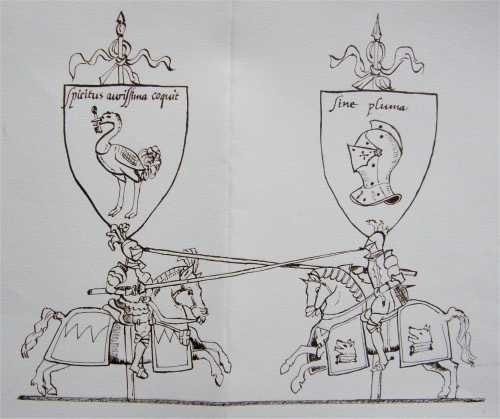

The bulk of the body of the text is in Scots. Mixed language was not unknown in formal declarations in Scotland. The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland include a declaration on November 13, 1516, which opens with a salutation in Latin, a declaration in Scots and a closing sentence in Latin. As this particular declaration deals with family matters - "concerning the bastardy of Alexander Stewart, commendator of Inchaffray" - it seemed appropriate to cite it as an example and use it to provide Scots usage for the birthbrief where family relationships were noted. I really should look to getting this material translated into Latin, as that was the lingua franca of the day and hence more likely to be used in papers intended for parts foreign. The script is in Italic hand, based on the humanist style handwriting of Mary Queen of Scots and her husband Lord Darnley. The Latin salutation is in Roman capital letters as in the Kinloch example. This was my first attempt at writing anything longer than my name in this script. It was difficult to keep even on the textured paper, particularly as the pen's ink flow was not consistent. I also made one major error in repeating two lines, which had to be erased leaving a rough surface which affected the replacement writing; the fixative also reacted to the ink in some places (where I had changed cartridges I think). Richard Kerr: ImpresaThe StoryThe Field of Cloth of Gold saw a great deal of combat over the three-week period, much of it arrayed in the full pageantry beloved of the kings of France and England. On the field Richard Kerr wore the family crest of a crowned dog's head atop his helm and presented a parade shield bearing the impresa sine pluma. One of the court attendants sketched a number of combatants, so Richard has a record of his attendance at this event and of the impresa he bore.

Imprese (sing. impresa) involved mottos, allegorical pictures and explanatory verse which were part of the basis for the high pageantry associated with tournaments. All elements were displayed or presented as part of the parades in opening ceremonies for tournaments and also in masques across Europe from the 14th century onwards. (Strong, pg 144; Young, pg 128).

The Nuremberg Tournament Book, recording jousts from 1446 to 1561, includes information on the tourneyers, their costumes, crests and the "humorous, often satirical, emblems that embellished the jousters' shields and horse's trappings". The tournaments of Scotland's James IV in the early 1500s were characterised by "elaborate allegorical themes" (Stevenson, 2006; pg 94) and James himself organised tourneys in which appeared the Wild Knight and the Black Lady. Early sources for imprese include the Classical masters, such as Ovid and Vergil, and the Bible; later sources include whole books devoted to imprese emblems and allegories. A number of portraits, such as that of the Earl of Cumberland (1590), include images of imprese shields along with their bearer and his tournament armour, or depictions of tourneyers with their main charge, badge or crest on their horse barding and an associated impresa accompanying them (Young pg 126; see here for more on impresa shields). The OutcomeThe impresa used here is first cited in print in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna, (No 78) with the accompanying emblem of a plumeless helm. Its theme focuses on how it is possible to serve without expectation of (or actual) reward, which suits the rather impecunious fortunes of the Kerrs of Jedburgh. (I've also used it as a suitable impresa for my lord and husband Bartholomew Baskin, as noted here.) The illustration is based on one which records tourneyers on horseback with arms, impresa and mottos, from an Elizabethan Accession Day tournament in the late 1500s (Young pg 126). A similar, earlier illustration is found in Starkey (1991), where tourneyers are shown from a 1524 tournament (pg 41). I have used that to show the arms of Richard Kerr, with his sine pluma impresa and his family's cur head crest. His horse also carries the St Andrew's cross of Scotland, and his opponent is obviously from the English side as he sports the cross of St George.

In fact, Richard is jousting with Francis Brian (aka Bryan), a Buckinghamshire squire who attended the Cloth of Gold in Henry's train and scored a prize (see Festival Book entry and 1520 jousting cheque). According to a Bryan family history, Francis was noted for the splendour of his apparel, was later knighted by Henry, and lost an eye in a tilting match. Clearly the depiction here is an accurate one! The illustration is ink on paper; the 1524 depiction was noted as an MS on paper, measuring 385 x 265mm and I have followed along those lines. Update: I keep coming across Francis Bryan. He appears as a rather raffish character, complete with eye-patch, in the third series of The Tudors where someone with some historical nous seems to have taken over the script-writing. There is correspondence to and from him in the collection of the Lisle letters. And I have seen a reference to him leading a troop at the battle of Pinkie Cleugh, where Richard Kerr died.... Richard Kerr: Jousting ChequesThe StoryFrancis Kerr took part in the tournaments which celebrated the marriage of Richard, Duke of York and Lady Katherine Gordon, in 1496. That were to be his last time facing a lance, but in 1507 he took his son Richard to Edinburgh, so that the latter might enter the Tourney of the Wild Knight. Richard's horsemanship served him well, and a copy of his jousting cheque joined those of his father's amongst the family papers. When Richard travelled across the water to serve in the Scots Guard at the court of Francis, he was fortunate enough to be able to take part in the magnificent tournaments of the Field of the Cloth of Gold. Richard Kerr paid a scribe to make a copy of the jousting cheque and roll of arms which showed him in illustrious company during those mock battles between the English and the French.

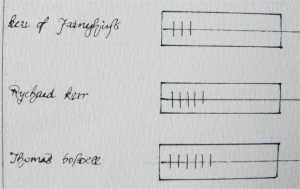

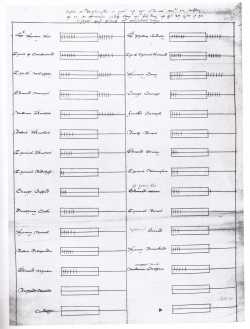

Jousting cheques and what are termed "occasional" rolls of arms provided clear indications of who had participated in a specific tournament (Friar & Ferguson, pg 50) and, consequently, were useful in proving one's right to participate in future events. Few of these ephemera survive, but those that do range from simple lists showing the names of the jousters and recording their wins and losses, through to more highly decorated versions that included depictions of the arms of those involved. Jousting cheques evolved over time, with some having a relatively complex set of marks to depict specific outcomes, while others just listed the courses run and outcomes. According to Starkey (1991, pg 46), the typical layout notes the challengers on the left and the answerers on the right. The various marks around the box indicate where the blows have fallen - a marker in the upper line corresponds to a blow to the head; a mark bisecting the line indicates the lance has been broken; the lines outside the box show how many courses had been run. As far as I have been able to ascertain, there are no jousting cheques surviving from Scottish tournaments. According to Stevenson (2006, pg 62), the Scots did not have formally organised tournament societies, such as those found in Germany. James IV, however, was well known to spend up large on tournaments throughout the turn of the 16th century, with jousts held for Richard of York's wedding in 1496, for James' own wedding in 1503, Shrove Tuesday tourneys in 1505 and 1506, and some rather intriguing sounding celebrations in 1507 and 1508 dubbed the "Wild Knight" and "Black Lady" tournaments respectively (Stevenson, 2006 pg 91-94). Scottish chronicler Pitscottie notes: ...the fame of his iusting and tournamentis sprang throw all Europe quhilk caussit money forand knychtis to come out of strange contrieris to Scottland to seik iusting because they hard the nobill fame and knychtlie game fo the prince of Scottland and of his lords and barrouns and gentillmen. James was also known to encourage jousting and hold small tournaments while his army was on campaign. During the Border raids of early 1487, costs are noted for replacement jousting spears (Stevenson 2006, pg 83). Although the main focus on the Field of Cloth of Gold was on the high nobility of kings and dukes, the jousts, tourneys and barriers held over the two-week period involved a great many participants. Barber & Barker note that the "challengers arrived in 14 bands averaging 10 each", holding single combat tourneys and fighting on foot. A jousting cheque from this event survives, depicting the combatants and their outcomes, along with their arms. The OutcomeParticipation in tournaments was normally restricted to knights and evidence of such participation was valuable support for a family's claim to nobility

Given Barber & Barker's statement above, it makes sense that proof of participation in a formal tournament would be regarded as important enough for a family to keep. Such information could prove an entrée to most tournaments on offer around Europe (although by the mid-1500s much of the enthusiasm for tournaments had passed). The first jousting cheque presented here is a simple list, noting the names of those involved and the outcomes of the bouts. It is generally based on extant cheques from 1516-1588, all of which are similar in approach. The names on this cheque reflect noblemen active during the 1503-08 period when James IV sponsored a number of tournaments at his court. Not all those involved had formal titles - Thomas Boswell was one of a number of young gentlemen who are recorded as having acted as "squires for the barres". Surely these lads had a chance at a tilt (the king himself was in his early 20s at the time). The names were cross-checked from a variety of contemporary sources, most usefully Balfour Paul's publication of the Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland for various years and the Parliamentary records likewise.

The extant 1516 cheque was on paper, measuring 437mm x 307, and I have followed that generally in this production, using A3 paper as a close approximation. Despite looking at half a dozen different cheques, I have yet to completely figure out how they worked in terms of markings (but then the experts also disagree as to the implications of the marks at times). So I copied the markings used in a later cheque, as the 1516 one is only partially preserved.

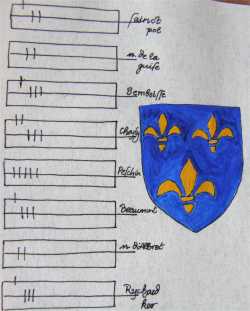

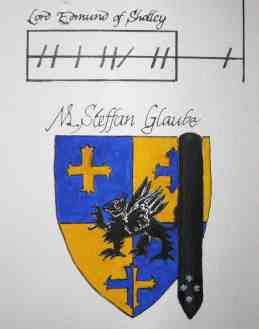

Richard Kerr's jousting cheque from the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520 is based on the original one held by the Society of Antiquaries, which is something of an armorial crossed with a standard jousting cheque, described by one commentator as a "hybrid". The names are those of people recorded as in the trains of Francis I and Henry VIII at the meeting and, where I can identify them, actual combatants. The arms are ones in use by the family of those named, if not the particular individual, as far as I could ascertain.

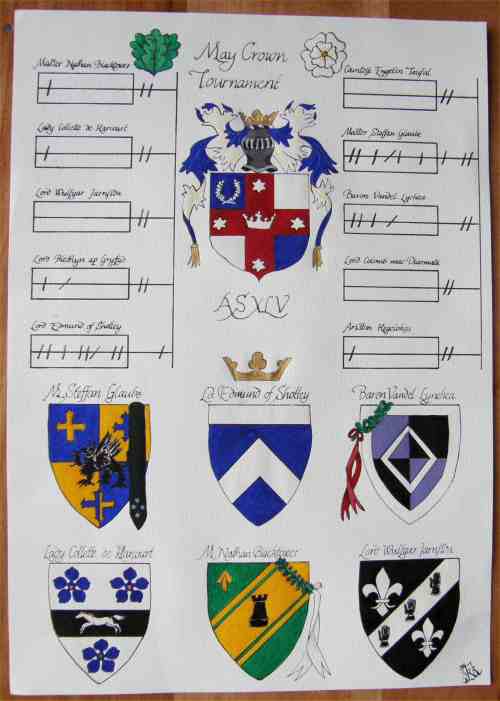

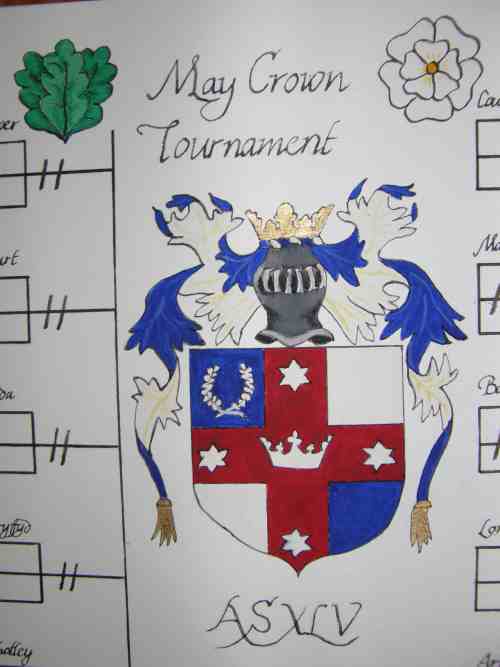

The cheque depicts who fought for which side and how they did in their bouts. As with the original it has arms indicating the side (ie France and England) and arms of some of the individuals involved. Unlike the original, the royal arms are not depicted with the collar of the Order of St Michael (for the French side) or the Order of the Garter (for the English), as the combatants are a mix of higher and lesser nobility, from counts and earls to knights and squires. I haven't been able to find a copy of the original cheque which allows me to see the names clearly, but I suspect that they were of the highest-ranking combatants. The original was on vellum, measuring 365mm x 273mm, possibly a more valued approach than paper as a reflection of the additional effort taking in depicting the arms and colouring them. I have produced Richard's version on parchmentine as the best alternative I had available, with goache as an acceptable period-style colouring agent and all the penwork done in black ink. May Crown Tourney Jousting ChequesI was showing the various papers at the Laurel Prize Tourney at Festival AS44 and His Grace, Sir Cornelius Von Becke asked if I would do a cheque for May Crown Tourney. I ended up producing a printed version to give away to the populace. It showed the tourneyers, the arms of those who had them registered, and the Line of Lochac on the back to pay homage to previous winners of the Crown of Lochac.The intro cited Rene of Anjou's reasons to tourney: For Honour! For Honour! For Honour! And then provided a little bit of explanation: And so that you might record such honourable deeds, herewith a tournament cheque of the style and nature as such may have been written upon the lists at Elizabeth of England’s Accession Day tilts or in France at the Fields of the Cloth of Gold. Regard well the noble combatants and make such marks as to note their bouts, whether victorius or not as ye will. Know that each such cheque may have divers marks as is deemed acceptable by each count-keeper. It was gratifying to see people using their jousting cheques to track how the tourney progressed, from the late scratchings of Duke Alfar and Angharad through to the tightly contested final. As with the extant cheques, different people used the scoring boxes differently to mark how the combatants fared.

Blank Jousting Cheque (PDF)

Illuminated Cheque for Coronation

This was the third time I'd ever used goache. That, and my general lack of artistic ability made me a tad nervous about attempting anything too fancy, but I was pleased with the shading effects I managed to get in the helm and the mantling which formed part of the Kingdom's achievement of arms (themselves modelled on the one used on AEdward and Yolande's instant AoA scrolls). I did learn in the course of the project that one should not expect waterproof ink to be waterproof and that it was a bad idea to paint while my hair was still dripping wet from a shower....

I used the Kingdom Arms with oak leaves and a rose to represent the King's and Queen's sides respectively. And I placed a crown above the arms of the winner, with wreaths on the arms of those who took the chivalry and valour awards (with the white and red ribbons respectively); the Champion of Lochac has the Champion's baldric draped over his arms.

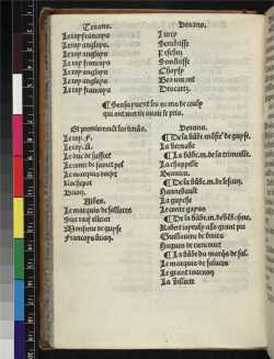

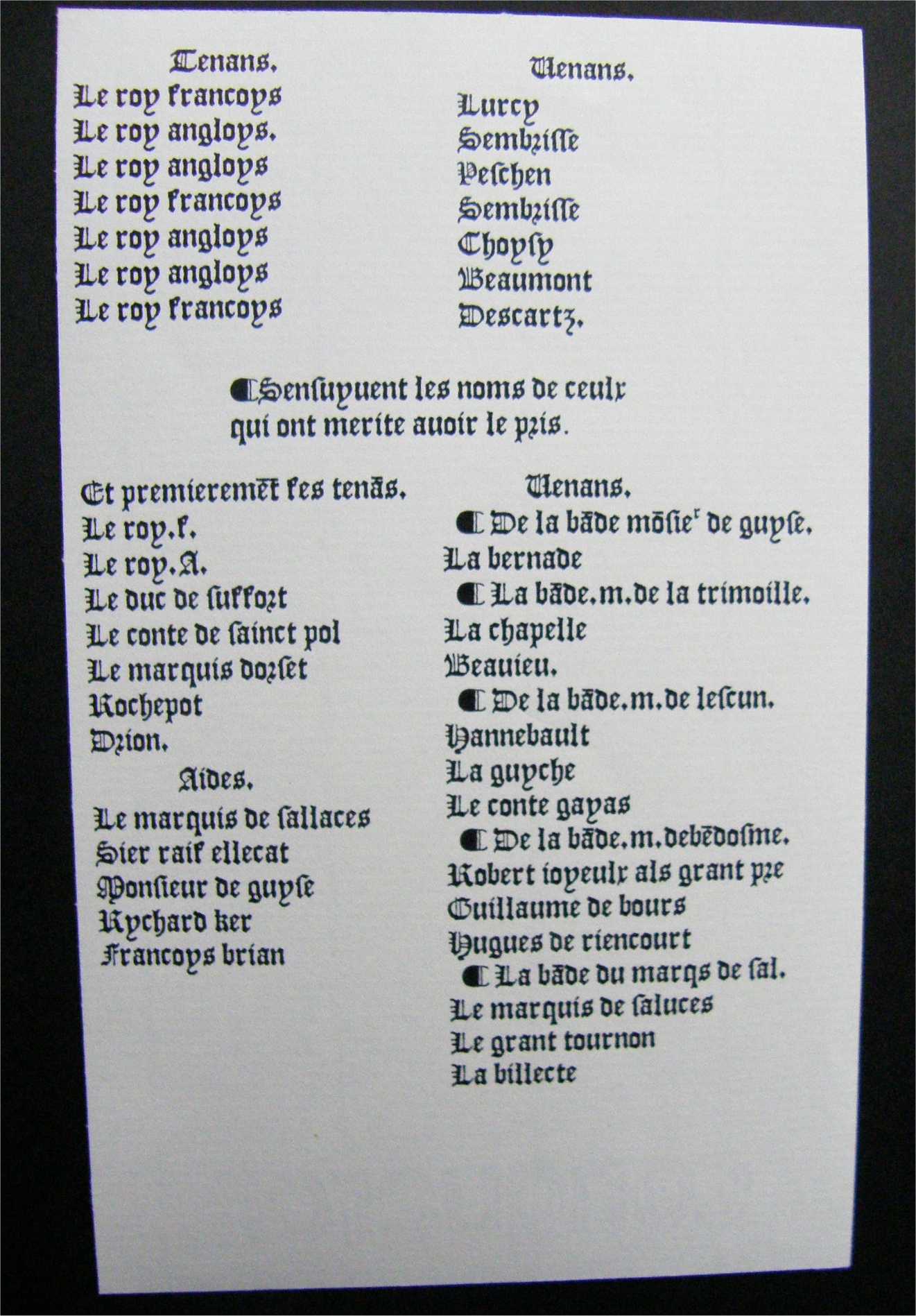

It was another useful project to practice my late-period handwriting and my less-polished goache and gold illumination. My lord Bartholomew took it to Midwinter Coronation to present to His Majesty Edmund of Shotley on behalf of the cheque patron Sir Cornelius. Richard Kerr: Sheet from a Festival BookThe StoryAfter the Field of Cloth of Gold, a Parisian printer produced a festival book recording the event. Richard was pleased to find his name amongst the list of prize-winners, and bought a spare copy of the sheet that showed his placing to carry with him. The BackgroundFestival books were the souvenir programmes of the day, listing who had attended important events, eye-witness accounts of what happened (sometimes even by actual eye-witnesses!), reports of sporting competitions, and ballads and poems in honour of the higher-ups. In 1520 Jean Lescaille printed a festival book, Lordonnance et ordre du tournoy, ioustes, [et] combat, a pied, [et] a cheual, celebrating the encounters at the Field of Cloth of Gold between the forces of Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France. Contained within that book was a list of prize winners (pg 52, British Library), citing various team members of the tenants and venants in the pas d'ármes combats that formed a part of the tournament rounds. In the British Library's commentary on their extensive collection of festival books, it notes that such works "provide the names and relative standing of prominent courtiers and citizens", though it does go on to admit that festival books do not always provide an accurate record of events. Helen Watanabe-O'Kelly goes so far as to say: The authors of such works see no problem, therefore, in amending or altering events to suit the political purpose of the moment, inventing or expunging from the record participants, paintings, inscriptions and even whole performances. So what better recommendation could one have in terms of producing a slightly amended version of such a publication….

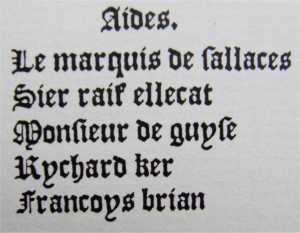

The OutcomeI have reproduced a very close approximation of the page of prize winners from Lescaille's work, showing that one Rychard Ker had been an aide on the tenants side of the Cloth of Gold combat and was listed as a deserving prize-winner in the company of such luminaries as the Marquis de Salluces and Sir Raif Ellecat.

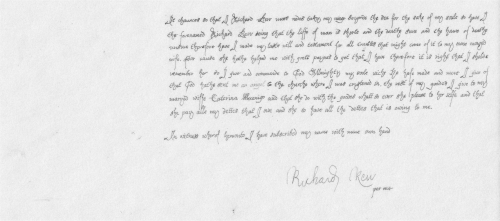

I used the JSL Blackletter font developed by Geoffrey Shipbrook based on period fonts of this type. The font is very close to that used by Lescaille, with only some small differences in the treatment of descenders and some of the capitals. The font includes a form of long s, the alternate r and the ability to use macrons to indicate abbreviations as per standard scribal/print usage from medieval times (Leedham-Green). Judging by the scale provided by the British Library in its selection of pages, Lescaille's pages were approximately 18 cm x 11 cm. The font and placement of material were estimated using this scale. The paper was sized for it, and is Conqueror laid bond which is comparable in style to the high-rag paper used in period printing. I had considered printing the verso page to give the same bleed-through effect as on the original, but the verso has yet to be scanned by the British Library. However, it's not uncommon for printers to this day to keep misprints and recycle the paper, so it would not have been unreasonable for Richard to be able to find a copy of the prize-winners' sheet by itself. Richard Ker: His First WillThe StoryIt seems that my father did something which necessitated him feeling the need to go on pilgrimage for the sake of his soul. It was not a thing he ever talked about, but it was sufficiently important to see him leave his new wife in Venice and travel across the breadth of Europa to Santiago de Compostela. This, his first will has been kept with the family papers, along with some other momentos of his travail. It wasn’t uncommon for people in uncertain times to make a will to cover any eventualities in case of their death – men before battle, noblewomen preparing for childbirth or, in this case, a man undertaking a long journey. The wording of Richard Ker’s will is closely based on that of Deryk Leke, prepared on June 5th 1546, and recorded in the London Consistory Court Wills (see entry 242 in the London Record Society transcription here). The wording caught my eye, having a very human touch to it, particularly with regards to his trust in his “owne maryed wife”.

It chaunces so that I Richard Kerr most nedes taky my viage beyonde the sea for the sake of my soule, so have I, the forenamed Richard Ker, seing that the liffe of man is shorte and the deathe sure and the howre of deathe unsure, therefore have I made my laste will and testament, for all trobles that myght come of it to my owne maryed wife. For cause she hathe helped me with grett paynes to get that I have, therefore it ys right that I shulde remember her, so I geve and commende to God Allmyghty my soole wiche He hafe made and more I geve of that God hathe sent me an angel to the churche where I was crystened in, the rest of all my goodes I geve to my maryed wiffe, Caterina mocenigo, and that she do with the goodes whatt so ever please her selfe and that she paye all my dettes that I owe, and she to have all the dettes that ys owyng to me. Unlike Richard Ker, Deryk had his will properly witnessed and dated. The layout of Richard's will is based on typical layout that I have seen; it is on parchmentine, as you'd want this sort of document to survive. The handwriting is a form of secretary hand in sepia ink which I am using consistently for anything written by Richard, with his standard signature (based on that of Richard Plantagenet). The original will consisted of three sheets of paper sewn together, being the English version, the Dutch version and a blank sheet. If I get really enthusiastic, I may see about getting an Italian translation and attaching that to Richard’s will. Thanks for a RescueThe StoryAfter Mother died along with my newborn brother, my Father and I left Venice to travel to Scotland, a land I had never seen. Our first attempt to travel by sea was not successful -- a huge storm battered our small vessel and we thought we were like to drown. We crept back into the safety of the lagoon and my father donated money for an ex-voto to be hung in our church before we set off once more, this time over land.

A series of these paintings, displayed in the Museo Storico Navale (Naval History Museum) in Venice caught my eye -- clearly they were telling a story. It turns out that they were ex-votos, votive offerings to Mary to show gratitude for her intercession in a time of crisis. Tingle notes that "while votives were commonly deposited at healing and other shrines, maritime communities have been particularly prolific generators of ex-voto acts and objects. For the most part, they result from the experience of calamity at sea. The seafarer, in the presence of natural elements which he or she could not control, having exhausted all other possibilities of saving him or herself, turned to supernatural powers" (pg 210-122). As with many of the maritime ex-votos, common throughout the 15-18th century, the Madonna and Child are shown "sitting snuggly on soft clouds" (Cuschieri) and surrounded by heavenly light, looking out over a vessel tossed on stormy seas. The Foundation Per Grazie Ricevute's article on ex-votos says that: This typical situation of the eternal fight between man and sea is depicted in many ex voto dating from the 15th Century. Three centuries later, other tablets included a new danger: the threat of Turkish boats bearing flags with a half moon and armed men dressed in red with white turbans. The initials VFGA stand for votum fecit gratiamque accepit, or vow made, graces received. This makes it a true ex-voto offering per grazia ricevuta, for thanks given after the divine intervention has been received (Jacobs, pg 7). There is another votive variation which is made in hope of receiving an intercession. As it happens, I painted the initials as NFGA, reading an asterisk as a downstroke of an N on the exemplar I was using -- clearly father had employed an illiterate limner! I'll see if I can modify that "typo". Painted tablets (tabulae pictae) began to be popular in the early 1500s, though variations had been around much longer. Votive offerings began to populate sanctuaries and churches. Even today, according to Jacobs, more than 1,500 15th-16th century tavolette votives can be found through Italy.

Maritime votive tablets were painted on canvas, wood and clay. My one is on a modern canvas (a birthday present from my daughter who was delighted to see it used). I have covered the modern staples with a leather binding; many period tablets were not framed in any fashion, so I figure this is not too inappropriate a modification. One of the typical features of the ship tavolette is that they were fairly badly painted, naively if one wishes to be kind. That encouraged me to have a go. Not all were that primitive -- there are many ex-voto paintings which are high art by Masters, such as Mategna's Madonna della Vittoria, and plenty of gold and silver votive offerings for assistance with health issues. Other maritime ex-votos consisted of material objects such as broken hawsers. anchors and ferramenti, or the model ships, seen suspended from the ceiling in churches from Scandinavia to Italy. Edward III left one at the tomb of his father in thanks for deliverance from a shipwreck. That might encourage me to find a boat model to make up -- something I've watched my father do. (As an aside, in 1600 Pope Urban VIII declared ex-voto as voto non grata, following on from the Council of Trent frowning upon them as an abuse possibly leading to idolatry or superstition. They began to fall out of favour around the time of the Reformation, but hung on until last century when thousands and thousands were turfed out of the churches and into the flea markets of Italy. Tingle; FPGR) References katherine kerr: Heraldic Visitation, Family TreeThe StoryAfter leaving the French court, Richard served in the conditierre band of Gionvanni della Banda Nera, which led him eventually to Venice, where he married Caterina Mocenigo, of that ancient house, in 1526. Richard returned to Scotland in 1537, with a young daughter in tow, his wife having died giving birth to their second son who did not long survive her. In 1562, as the heiress to the family arms, my brothers having died young, I asked a visiting herald to draw up the notes for a family tree so that I could have a record of my family line. The BackgroundAs within the SCA, period heralds and heraldic authorities became concerned over the possibility of people inappropriately displaying arms, using arms that were not registered to them, or using incorrect arms. From time to time, starting in the 15th century, heralds would make concerted efforts to track and note arms in use by families, along with their family lines of descent. Such visitations could be informal, as part of normal social functioning, or prescribed, with people summoned to set interviews and required to bring proof of their descent and authority to use the arms. Those who were found to be unlawfully using arms had the usages - including funerary monuments - removed or even defaced. There are many recorded examples of herald visitations, particularly in the sixteenth century when systematic records were being made, in England by the College of Arms and in Scotland by the Lyon Court. (eg The Visitation of the Countie of Lancashire made by William Flower Esquire, alias Norroy King of Armes, anno Domini 1567; Harleian Manuscript; see Philips). Henry VII established the visits by Garter and Clarenceaux in 1489 with aim of producing pedigree books (Wagner, pg 31-32).

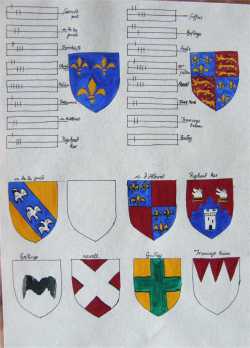

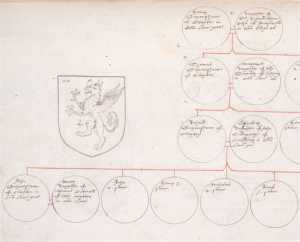

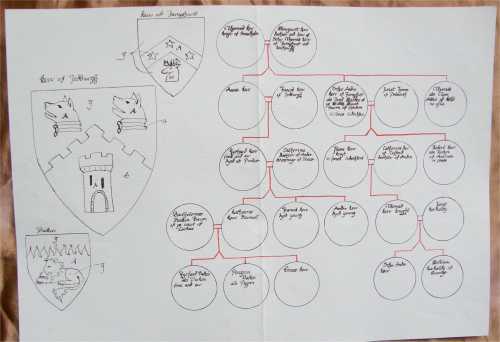

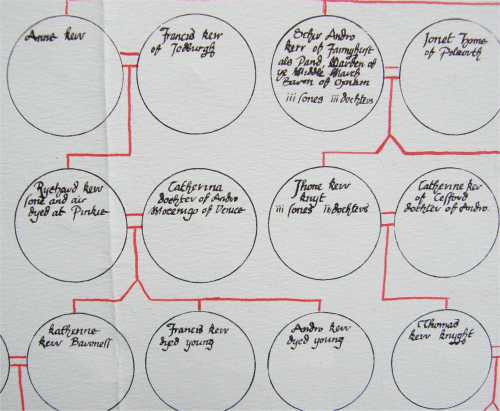

The heralds would quiz the family about their descent, record the pedigree, sight seals, monumental inscriptions and other examples of armorial bearings, sketch or "trick" the arms and produce a record that would later be formally drawn up for official records such as the Library of Visitation Books (Lysons; Wagner pg 32). "Tricked" arms are basic pen sketches with shorthand indications of tinctures and notes on charges. These were used as quick records which could later be properly painted into formal rolls or armorials. In addition to direct lines of descent, pedigrees would often include quarterings as a result of inter-marriage, the descent of heraldic heiresses, and, less commonly, important dates, often relating to documents or events, rather than births or deaths per se (Phillips). However, it is clear that, as with rolls of arms, there was no guarantee of accuracy, particularly when recording pedigrees that stretched back over three or more generations. Ironically, the shorter the pedigree, the more likely it was to be accurate, or at least without the fanciful additions of ancient heroes or mythological beings that are found on some extant examples. There are many family trees which are beautifully painted and highly complex in design, such as the 1583 tree described by Balfour Paul as "the most beautiful family tree in Scotland", being covered in flowers and leaves and animals all "executed with great minuteness and beauty of colouring" (Balfour Paul, Pg 206). Sadly I haven't found a depiction of this (yet), but one day…. The OutcomeThe simple family tree and tricked arms depicted here are based on the extensive records of Grimshaw of Clayton from an heraldic visitation of Lancashire by William Flower (Norroy) in 1567. The Grimshaw records dealt with one line of descent; others were more complex, showing descent through a number of lines.

I chose to depict not only the Jeburgh Kerrs (my own persona family line) but to demonstrate how they were related to the historic Kerrs of Ferniehirst, a notable Border family who contributed a great deal to the most "romantic" aspects of Scottish history throughout the 16th century and beyond. I wanted to take this line down as far as William Kirkaldy of Grange, as I've always had a soft spot for that particular gentleman who fought for Mary Queen of Scots and was besieged in Edinburgh Castle. The text has been adapted for Scots usage, rather than the northern English of the Grimshaw example (eg sone for sonne, dochter for daughter).

Many of the herald visitation notes are simple line depictions; I liked the Grimshaw one with its circles and red lines, and followed that variation. While it doesn't have an example of the "jinked" lines to follow the descent, these were common enough in pedigree diagrams, such as those produced for the heraldic vistation of Wiltshire in 1565 (Slater, pg 42).

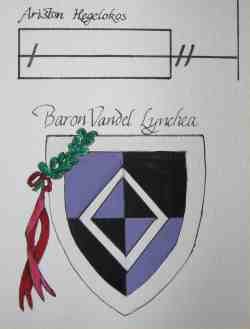

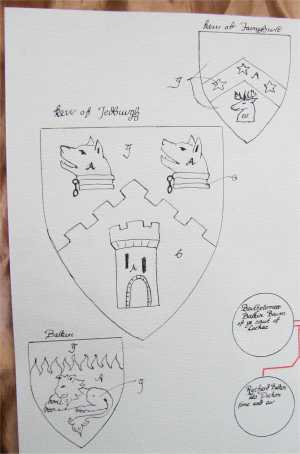

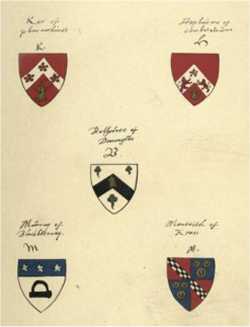

The tricked arms depict the family arms of the Kerrs of Jedburgh, as well as the arms of the Kerrs of Ferniehirst, and those of my lord Bartholomew Baskin. They use the standard abbreviations found in period tricked arms to denote the tinctures (eg b for azure/blue; A for argent etc). The Grimshaw records and those of other herald visitations do not have specific information on the nature of the original manuscripts. I have assumed, judging by the script used in the diagram, that the depiction referenced here is contemporary with Norroy's visit; the printed version is clearly a later transcription. I have estimated the likely size of the paper based on the proportions of writing to circles in this instance, and believe that it would be likely to be a little larger than the A3 watercolour paper I chose to use as a convenience. The handwriting is based on secretary hand, as in the Grimshaw material, with the addition of some peculiarly Scottish handwriting elements. The circles have been accomplished with a pen and compass, which is what I am fairly sure was used in the Grimshaw pedigree, based on careful examination of the ones drawn there. The rose-scented red ink had been bought from a calligraphy shop in Florence and was applied with a glass spiral-headed dip pen. This meant hand-drawing the lines without the use of a ruler, as appeared likely in the original. One of the most interesting aspects of this particular segment of the project has been the development of the timeline and connections that gives this family tree a very real sense of history. I had to initially decide who had been born when and what had happened in their lives. Thus I "discovered" that Grandfather Francis was killed during one of the English incursions over the Border, and Father died at Pinkie Cleugh, along with the remnants of the Scottish nobility that had managed to grow to maturity since the disastrous Battle of Flodden. katherine kerr: Roll of Arms, ArmorialThe StoryAny family of noble descent is proud to be able to point to their depiction in local armorials and rolls of arms. Richard Kerr died at Pinkie Cleugh, leaving his daughter as sole heir to the arms of Kerr of Jedburgh. These were recorded in a roll of arms by Sir Robert Forman, Lyon King of Arms, in 1562, along with those of several hundred ranking Scottish noblemen. When the opportunity arose, my lord and I were pleased to be represented in the Armorial put together by the Lord Lyon Robert Forman recording Border families. It shows my lord Bartholomew Baskin with his arms, as well as the Kerr of Iedbrvght family arms I brought to our marriage as heraldic heir to my father. These documents are kept close, along with others from the family, so that our sons can prove their descent and right to bear arms. The BackgroundA variety of types of rolls of arms and armorials have been used throughout period from the 13th century onwards to record the arms and heraldic achievements of nobility. The initial rolls were just that - long rolls of vellum, such as the well-known Rous Roll of the 1480s; later collections were produced as bound books. Rolls could be organised in a variety of ways, such as regional rolls covering an administrative area; illustrative rolls accompanying chronicles; or general rolls (Friar & Ferguson; pg 50). The first Ordinary of Arms, where the blazons were listed alphabetically based on their charges, were produced in the early 1300s, such as Cooke's Ordinary and the Baliol Ordinary. There are a number of Scottish armorials and rolls, both native to Scotland and recording Scottish arms for those active on the Continent. The earliest local example is the Scots Roll, dating back to 1455, with the mid-1500s seeing a jump in the number recorded such as Sir David Lindsay's Armorial (1542; Secundus 1599), Queen Mary's Roll (1562), Forman's Armorial (1562) and the Seton Armorial (1591); their contents are listed online by the Heraldry Society of Scotland. They vary in production, ranging from simple depictions of shields through to detailed depictions of personages of note in heraldic dress. In the late 1800s, Robert Riddle Stodart produced a facsimile of Scottish armorial bearings, dating as far back as the Gelre collection of the 14th century (although French, it had a section of Scottish arms and crests). Contained within this collection are examples from Forman's Rolls (1562), including a number of Ker arms (eg Ker of Fernihirst, Plate 16). Sir Robert Forman was Lyon King of Arms, appointed in 1555, and his roll included the arms of 267 knights and landed gentlemen. Also included are the Kings and Nobility Arms, the first edition of which Stodart dates to Mary's reign after her second and before her third marriage (pg vi). Unlike the others, these include full achievements: helms, mantlings, crests, mottoes and supporters. Examples from the well-known 1542 manuscript of David Lyndsay of the Mount are represented, along with items from the Workman MS of 1556-66. It is interesting to note just how many errors are recorded in the rolls examined by Stodart. For Kerr alone, one depiction shows Kerr of Ferniehirst arms as sable and argent, instead of gules and argent (Plate VIII); others substitute cinquefoils for mullets. The latter is blazoned in what the Heraldry Society of Scotland calls Queen Mary's Roll of 1562: Ker of phernihirst Gules, on a chevron Argent three cinquefoils Gules and in base a stag's head erased Or. The Forman's Armorial has the correct blazon: Kar of Fernyharst Gules, on a chevron Argent three mullets Gules and in base a stag's head erased Or. Stodart's facsimile shows other Kerr arms, including those of Cessford, Samuelston and one that is simply labelled "Ker of". The OutcomeI have put together a page from Forman's Roll, which depicts four Ker/Kerr arms and the arms of Colville, a related family. Ker of Ferniehirst has that family's standard arms, as does Ker of Samuelston (including the rather odd-looking version of their sable unicorn) and Colville. The unlabelled Ker arms in the centre are close to the ones in the original Forman's depiction, but have the argent chevron of the Kerr clan, rather than the or chevron of the original (likely erroneous).

Ironically enough, when I came to paint this page, my mind went blank and I gave the Kerr of Jedburgh arms an argent chevron in line with the other arms, rather than the per chevron embattled line of division that these arms should have. This does, however, replicate the type of errors found in the original, so I decided to let it stand as a reminder that heraldic mistakes are a relatively common feature, even in the most formal papers. The script is a version of secretary hand, to match the script used in Forman's Roll. While the depictions of the charges may look a little cartoonish, they really are based on the various period examples from Stodart. He was sufficiently bemused by the original artwork to say: On its artistic side, medieval heraldry is seen in an animated and, one may fairly say, a slap-dash mood. The quaint spirited lions, the admirable boar heads, the extraordinary conceptions of the griffin of Lauder, the unicorn of Kerr of Samuelston, the otters of Meldrum, the lion faces of Macgie, the parrots of Pepdie, and the other more or less successful endeavours to depict animal forms, are interesting and entertaining additions to the heraldic menagerie. As to the ordinaries-bends, chevrons, etc.-the paint was splashed on without a pause for measurement or the ruling of a line; to such an extreme in the case of the cross fleury of Carlyle that it would be unrecognisable unless one knew what it was. Nor did the artist even slacken his headlong career to make his shields approximately symmetrical. I suspect that few, if any, of these depictions would pass muster with the SCA heraldic authorities! The armorial depiction was similarly amateurish, more because of my lack of talent with a paintbrush than as a result of following the period material. It would have been nice to have been more artistically capable, as I based the armorial entry on that of the Seton Armorial of 1591, which is more sophisticated than the earlier rolls of arms. That armorial has a large collection of historical couples represented in relevant heraldic clothing or with coats of arms displayed in some fashion. I have used the example of James IV and Margaret Tudor as the basis for the depiction of Bartholomew Baskin and katherine kerr.

While the Seton Armorial is later than my mid-1500s period, I do know that comparable armorials were in existence at that time. A similar document dated to 1540-1550 is a manuscript which depicts 22 pen-and-ink drawings of the founders and patrons of Tewkesbury Abbey. It is describer by Blunt as a "small quarto" measuring 6 inches x 5 inches (pg 5). As I haven't been able to find a description of the physical properties of the Seton Armorial, I have used the Tewkesbury armorial as the example for sizing, with parchmentine as the base material. Final CommentsThis project has led to a huge branch of personahood opening up for me, and one which is going to prove very rich in ideas and inspiration. I had an interesting talk with a pair of calligraphy and illumination folk keen for me to do more calligraphic work, but I'm not into calligraphy -- I'm into handwriting! I keep looking at the various examples I have of Mary Stuart's writing and figure I can write as messily as that. I thoroughly enjoyed the various hands I developed for this project, but I'll be concentrating on developing a reasonable humanist hand, which is not really calligraphy at all. Between having the hand and finding lots of useful resources for information and journal writing, I figure that I can spend a good deal of time expanding on this initial production base. Now where did I put that pen...

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||