|

|

Peerage Elevations & EntertainmentsHugh de Calais: Quest for the FoundlingOthers My Peerage Stuff

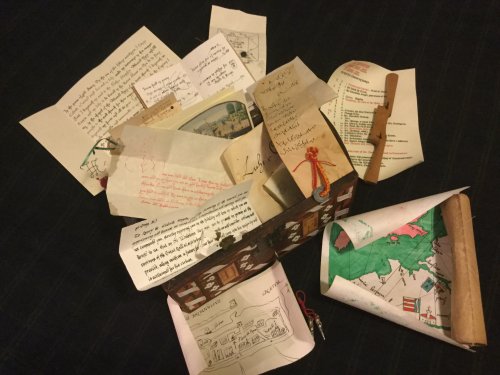

I seem to have become involved in customising peerage elevations or providing elevation-related entertainment. I blame Master Nicodemus Novello for that -- he attended a class I was giving on persona development via paperwork (ie amassing letters, bills, wills and the like) and made a chance remark, and it all grew from that... Quest for the Foundling : Canterbury Faire 2017I gave a class at Festival in 2016 regarding how you could use documents to build up a persona and inspire other projects. While discussing various interpretations of an orphan name tag found amongst my “father’s” possessions, Nicodemus remarked that such things could be used to form the basis for an interesting quest. A day later, when Hugh de Calais was invited to join the Laurels and opted to do so at Canterbury Faire the following year, the Quest for the Foundling was born. The general concept developed very quickly – the Quest would start with the reading of a will; the associated inventory would list the items being hunted for; and documents in the deceased’s coffer would provide clues to the whereabouts of the items and the identity of the unknown heir. With luck, Hugh would play without twigging to his central role in the Quest; that is, he had no idea what was being planned. I started to ask various Laurels if they would be interested in providing a gift for Hugh on his elevation and got enthusiastic buy-in, especially once I’d explained how the whole thing was to be framed. The main concern seemed to be could they do justice to whatever item they volunteered to make, to meet the sort of standards that Hugh was worthy of! So I then had the fun of matching the items offered to appropriate documentation and building up the story of the life and times of one Henry de Calvile, a soldier-merchant residing in Calais until his death in 1376. He would be Hugh’s unknown father, with his last will, testament and inventory being the thing to kick the whole quest off. That time and place was chosen to match the chronology of the Company of the Staple (Inc.), an historical re-enactment group to which Hugh de Calais belongs. From there it was a matter of intense on-going research to produce items and documents to match, building up the chronology of Henry’s life and providing reasons for why his possessions might be scattered around the countryside. All this without making it too obvious that the Quest was based in Calais or pointing too obviously to Hugh as the foundling. The reading of the will was scheduled for the opening day of Faire (Monday), with the instructions noting that the quest would run through the following four days. The document coffer (made by Master Edward Braythwayte) with all its documents (made by me) was turned over for the questers to examine, and copies of the inventory and quest rules provided. I had to make a nasty nylon cover for the coffer as Ed had carved the leather with symbols referencing Hugh. To keep the Quest running, and to string out the various clues, some of the inventory and a couple of major clue-providers were scheduled to appear on Wednesday (Magister Bartholomeaus as horoscope caster) and Thursday (Nicodemus as Cardinal Simon Langham), with the identity-based material released last. The final denouement was scheduled for Half-Circle Theatre on Thursday evening. The run-sheet with timeline, notices, interactions, props list etc ran to around 20 pages. I acknowledge that is it an act of immense hubris to develop a completely novel persona background for someone without their knowledge or consent (even more so when appearing to make him illegitimate, albeit acknowledged at the end!), but I was always confident that Hugh de Calais would take it his stride, appreciating the high respect and affection those involved showed by doing so. The Story UnfoldsMy aim was to build a coherent set of materials illuminating certain aspects of Sir Henry’s character, past and position, using the various promised items in conjunction with related documentation. Thus I had to think hard about what would be found where and why, then build a story around that that worked logically as well as chronologically. When I found myself wondering how medieval illiterate laundresses tracked their customers’ items, or dating letters after investigating how long it would take for a ship to get from Southampton to Calais, I knew I was in for a year of intensive, but entertaining research. The questers were told to consider the documents carefully, then act upon them. If they found any items, they were to come and tell/show me and then hang onto them until Half-Circle Theatre. As they were discovered, the items were crossed off the inventory posted on the Market Cross. This meant I could get any accidentally lifted items returned to proper owners, and questers would know which items were still in play. The questers were also told they would get one -- and only one -- chance to identify the foundling, but they had to keep quiet about it until the denouement. And the final important item of information was that they could take a document out of the box if they needed to, but only for a certain period; this was to alert them to the idea that they might need to present something in order to gain an item.

All the documents were based on as close-to-the-period textual material as I could find. It is all paper-based, rather than actual parchment, but follows general 14th-century practices. The various hands used for the different correspondence are based on typical handwriting of the period but simplified somewhat to make it more readable for the untutored eye. A Brief Background As a young squire, Henry de Calvile arrived in France in August 1342, along with 1,500 English nobles and men at arms, including his uncle (the historically real) Hugh de Calverley (aka Calvyle, Caverle, Kerverley, Calvile, Colville etc), under the command of the Earl of Northampton. The force served in the Breton war of succession which pitted the English-backed Jean de Montfort against the Counts of Blois over the Duchy of Brittany, and led on to the Hundred Years' War. Henry had a liaison with a Breton girl from Morlaix following the battle there in September, which resulted in the birth of a son on St David’s Day (May 24th), 1343, in the 16th year of the reign of Edward III. The foundling was taken to Avignon by Henry’s friend Simon Langham, later Cardinal Langham. Henry sent money to Avignon for his son’s upkeep, but died without ever meeting him. The Amour

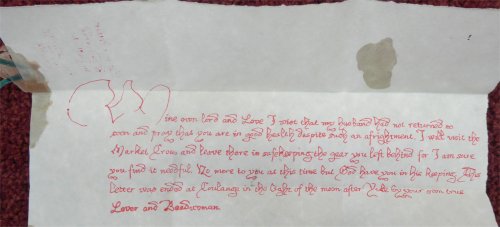

It's clear, if you read it carefully that the letter is telling an age-old common story: Yes, she's telling him she's pregnant and her father's not happy about it. And those blots in the letter are tear-stains. The writer's name is unidentified, but the initial A was selected as representing a very common starting letter for women's names in France in the 13-14th century (eg Aaliz, Agnes, Ameline/Avelinez). This letter doesn't contribute to identifying any of the specific items from the inventory, but does help to provide some background for the foundling's birth, and sets the scene to flesh out the story. In researching how to seal the letter, I came across references to women using their own hair in items of intimate correspondence. I figured that including a lock of hair would be acceptable practice, and used the pleated format and a cord for the seal (which has a fleur-de-lys symbol to emphasise the French connection). Technically the cord should have been sewn through the end of the letter for absolute security, but I wanted it to be readily openable for the questers. (NB the letter-locking formats used throughout the documents are probably closer to Elizabethan style than 14th century.) Youtube clips: here and here.) Safe-Conduct I had great fun distressing the parchmentine with a crème brulee blowtorch for a bit of textural interest. It provides a reason as to why Henry didn’t go through with a formal marriage to his love, though Cardinal Langham knows that they exchanged betrothal vows, which was generally considered binding. Clearly by the time Henry was able to return to Morlaix, his love had already died in childbirth. The Foundling's Name Tag

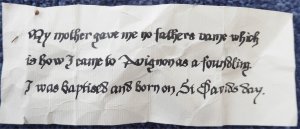

It was Erik Kwakkel's blog entry (and his other blogs and books) that really got me excited about ephemeral paperwork as a persona-building tool, leading to years of happy thinking, researching and creating, and, of course, this Quest. So based on this material, I made a name tag for the foundling with his birthdate, and the fact that he was carried off to Avignon. Simon Langham had connections with the Avignon papacy, and the writing used on this name tag matches the Cardinal's as used in his summons (possibly too subtle a point for the questers to notice, but it was good continuity). So the foundling tag read: St David's day is Hugh de Calais' real birthday (May 24). Interestingly, one set of questers decided that the period phrase "gave me no fathers name", rather than pointing to illegitimacy meant that the foundling had a generic by-name. That was part of what they considered evidence pointing to Hugh with his geographic byname -- totally wrong idea, but the right identification! The Foundling's Horoscope

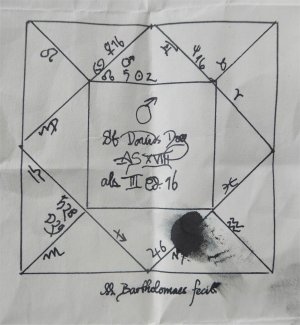

The period-styled horoscope notes the birth occurring in the sixteenth year of Edward III’s reign (1343) or AS18 (1983) on St David’s Day (May 24). The reading was taken from the astrological writings of Agrippa, Ficino and others, thanks to Christopher Warnock's handy Renaissance Astrology website with a bit of additional fudging to describe the foundling in more detail than the initial indications. For this reason, the Magister’s revelations were timed to occur later in the Quest. (The reason there’s an ink blob is because I absent-mindedly wrote in the position of Neptune, an unknown planet pre-1600!) Bartholomew dropped some strong hints about being available for astrological consultations at a certain time but, by the time that came round, the questers had already figured out the identity. A shame really, as I’d written a whole page of chatter and astrologically derived descriptions and comments, like this: Chatter, if questers don't present the chart: How could I be expected to remember a natal chart among the thousands I have prepared over my lifetime for everyone from Princes to merchants! Astrological reading: The Sun is in Gemini indicating a strong active body if thin of stature, dark of hair, with an agile mind that welcomes novelty. By nature Hot, Dry, but more temperate than Mars; a Masculine Planet, and in good aspect indicative of Fortune. Known to keep promises with all Puncutuality; speaking deliberately, but not many words, and full of Thought. Affable, Tractable, and very humane to all. Pretty descriptive of Hugh, I'd say! Henry's Will and Inventory

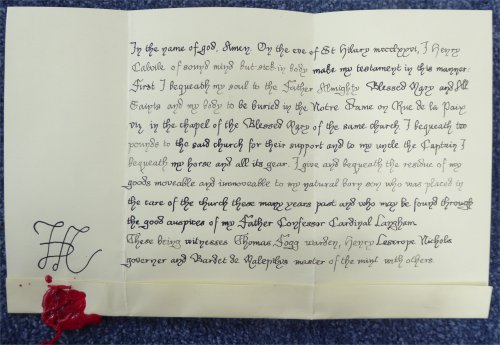

It is signed with a monogram formed from the initials HdC (as shared between Henry and Hugh). The witnesses to the wills are all recorded officers of Calais at the time, and the Father Confessor referred to is Simon Langham, then Cardinal of San Sisto Vecchio (Rome), residing in Avignon. The will itself is based on the 1489 will made by John Barone of Leicester, recorded in the British History archives of Lincoln wills. The accompanying inventory was basically a list of things the questers were expected to find by following the various clues from documents and people encountered along the way. It read: The true Inventory all and singular of the guids and chattles remaining of Sir

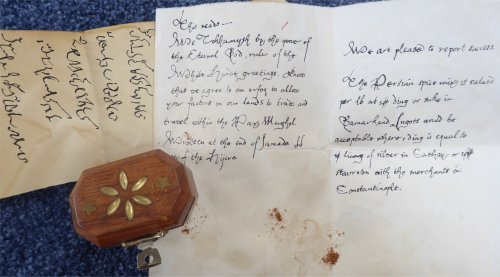

Henry de Calvile lately residing in the Captains quarters within the garrison, appraysed on xxist daie of December in the xlivth year of the kings reign. The Spice Merchant The ortoq covers business relationships, most commonly freedom to travel through the area controlled by the Horde leader, sometimes relief from customs and taxes. The ortoq offer is based on a letter in Persian written by Guyuk Khan to Pope Innocent III in the mid-13th century.

The English translation: With a covering merchant note: We are pleased to report success. The Persian spice mix is valued per lb at 200 ding or suke in Samarkand. Ingots would be acceptable where 1 ding is equal to 50 liang of silver in Cathay or 4000 stavraton with the merchants in Constantinople The currencies are ones in use during the 1300s (Vogel, Appendix 6) and cited in Henry’s accounts journal. This item was added in part to provide a link with the CF theme of Marco Polo’s travels along the Silk Road.

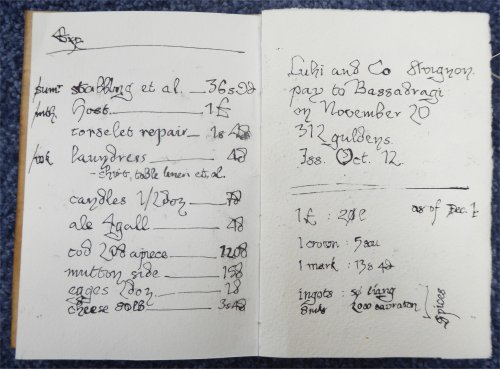

Account Journal

Anno 49 Ed. III. Oct. Henry’s income was based on that of a man-at-arms, and was paid by the Calais Master of the Mint of the time, Bardet de Malepilys. Clearly Henry was also taking money off the Castle Warden, Thomas Fogg, on a regular basis (cards? dice?). The stabling costs for his horse may seem high, but that was for the whole summer. The costs are based on 14th-century estimates from Kenneth Hodges' helpful Luminarium entry, amongst others. It also noted a large payment made to bankers in Avignon, along with exchange rates.

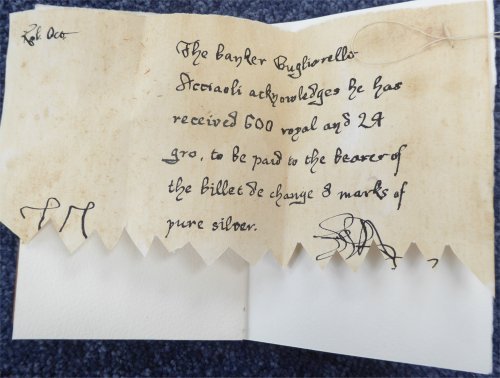

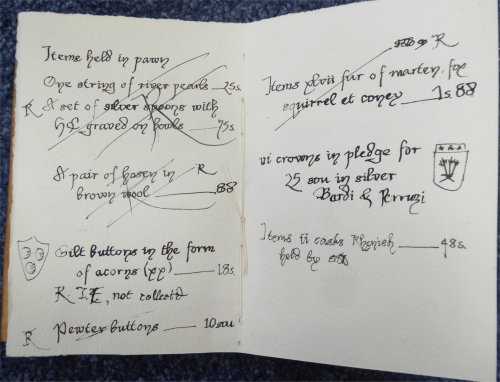

The banker Gugliarello Acciaoli acknowledges he has received 600 royal and 24 gro, to be paid to the bearer of the billet de change 8 marks of pure silver. Another section recorded the items Henry had in pawn to various merchants and bankers. The document was based on actual pawn records (albeit 16th-century Venetian, the only ones I had available); where possible, the prices reflect recorded costs for the late 14th century. The pawn listing for the Quest gift item (buttons gifted by me) includes a traditional three-ball symbol; this symbol was to be displayed at the Faire Market to identify which merchant had that item.

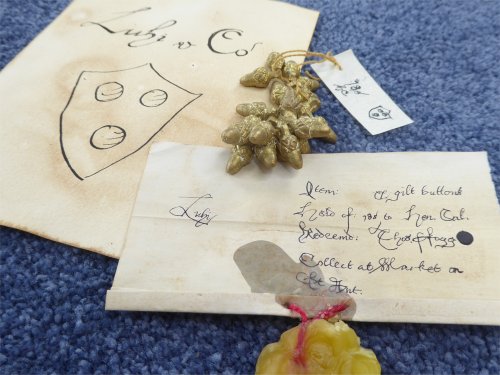

Tucked in the back of the journal was a pawn redemption ticket from the Luhi bank (which was based in Avignon at this time), showing Thomas Fogg had paid his debt through redeeming an item Henry had in pawn. The ticket has a beeswax seal showing the three balls. The idea was that the questers had to show the pawn ticket to redeem the item at the Faire Market on St Anthony’s Day.

At Market, Sir Sebastian laid out his usual pewter wares alongside 20 gilt acorn buttons next to a Luhi & Co placard showing the three balls of a pawnbroker. Sebastian had a range of lines to deliver, depending on what the questers said: Mentioned in another account journal entry were the Italian bankers Bardi and Peruzzi. They were bankers to Edward III; the Compagnia dei Bardi had branches in Bruges and Avignon (though by the 1340s they had both actually gone bankrupt as Edward reneged on the 1.5 million florins they had loaned him!). A bill of exchange, citing yet another contemporaneous banker, was sewn into the journal. This had nothing to do with the Quest itself, but added more period touches to the accounts – charters, receipts, notes and even tally sticks were commonly attached to manorial rolls and other accounts. References: The Brewer’s Letter and Note

The Brewer was set to grumble about Sir Henry being a man fond of his French wine and his French women. If the questers mentioned the letter, then they were told that: the gear is with the cooper as he’s still busy sorting out the barrels; the Brewer then provided a note to take to the Cooper. When players got to the Cooper, if they didn't have the note, they were told: More than my job's worth innit? That’s Sir Henry’s gear, how do I know you’re legit? I’ve been dealing with the brewers over this order. You want me to hand over somefing, you gotta have some notification that it's all right with the brewers or they’ll have my hide. Production of the note produced the spokeshave; like other collected items, they were told to keep it for the Half-Circle denouement. The note was based on a letter from Margaret de Lacy to Sir Robert de Vere (1245-1266), asking her cousin to return a knife that had been lent so she could send it off to her father (Moriarty, pg 113), with additional material from a 1479 letter from John Fawne to the Prior of Christ Church (Moriarty, pg 115). It has the symbol of the Brewers’ Guild with an R for the scribe drawn across the folds.

Merchant’s Correspondence

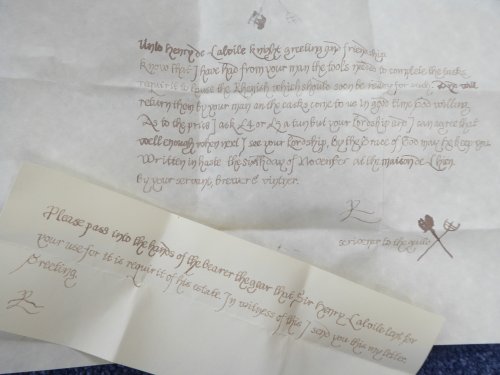

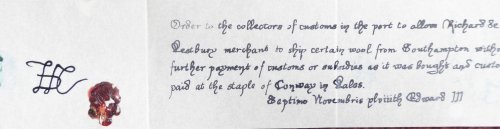

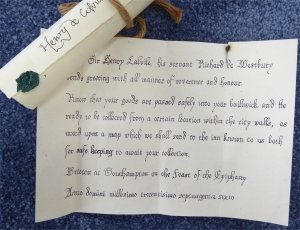

So interpreting the correspondence, the safe passage from Henry had been sent to England for Richard to bring goods over, as his short note on it indicates (also explaining why Henry had the safe conduct in his papers). The Order to the Collectors of Customs is based on one issued in 1370 and, being a letter patent, no seal is used to close the item. Richard uses a hemp tie and green sealing wax for his correspondence.

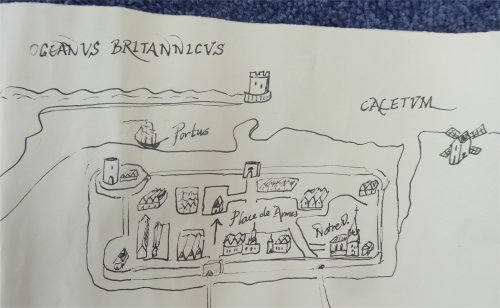

A follow-up letter explains more, with it pointing to the map to be provided a few days into the Quest, sent “to the inn known to us both” (ie Canterbury Faire's coffee house, the Mangy Mong). I added an additional interaction at the Mong, allowing an explanation for why an inventory item had been left there, as I was concerned that people would try to use the map as a “treasure” map for the site itself. The map was left out conspicuously on the Mong bench, with the length of wool on a shelf behind the bar. The Mong staff were given the following lines: If the questers sought further information, or tried bribery, then they were to be told that Westbury's man left something else behind: Map Westbury’s map of Calais is based on a number of depictions. Braun and Hogenberg drew the city for their map, included in the 1598 work Civites Orbis Terrarum. Although that was a much later work, it was possible to rework it to show the old citadel town with its Notre Dame Cathedral (referenced in Henry's will), market square and 13th-century donjon, using other images and descriptions of the town prior to later construction. Calais has had a lot of variations in the spelling of its name: Caletum (Braun & Hogenberg), Calesium (Hoefnagel), Cales, Calys (Minot). These usages were scattered amongst various documents as a clue towards identifying Calais as a place of importance for our foundling, Hugh de Calais.

The general map of England and France was based closely on that of the 1375 Catalan Atlas (also used for the Faire T-shirt logo that year, as it included images from Marco Polo’s travels). It has been simplified to make the town names more legible and to provide a few more clues as to the important points in the Quest. The rhumb lines run from the compass and from the town of Calais. I drew the map, scanned it, then treated the paper with an aging process, soaking and baking it in red wine vinegar, then illuminated it with coloured ink (yes, England really was that pink in the original, though possibly that was due to aging). The map was stored it in a balsamic vinegar-treated “leather” case. I could have made an actual leather case, but the vinegar treatment produces something reasonably close to parchment leather and is a lot lighter so unlikely to crush or damage other items.

Laundry Ticket and Proclamation

That is, I presumed each laundry order would be identified by wool of a specific colour attached to each item on the line; the number of items was identified on the laundry ticket by the number of bits of wool attached. Each ticket was in the form of an indenture with the owner holding one part and the laundress the matching piece, thus preventing misidentification or theft. The list of laundry charges, based on period costings, clearly was written by a professional scribe for the laundress to advertise her services to the literate eg Shirts iiid, Small linens id each, Woollen hose vd, Brushings iid, if velvet iid extra). The laundry item was one of the first to be developed, thanks to the prompt offer of a shirt from Mistress Miriam Galbraith. It also gave me a chance to allow for any additional sewn items that might come in late which would not necessarily be specifically identified in the inventory accompanying the will. As it was, I had various clues scattered about as to the nature of the items – references to laundry charges in the accounts journal, a comment about table linens going missing, a fine linen shirt and hosen made of baumwoole (the period German term for cotton) listed in the inventory. A number of items were pegged to a clothesline strung between the artisans' shelters at Coppergate. This meant Mistress Miriam could keep an eye on them and act the part of laundress should any questers approach. I also made up a proclamation based on one promulgated in Leicester in 1461 (Rawcliffe), and set it in secretary hand for posting on the Market Cross:

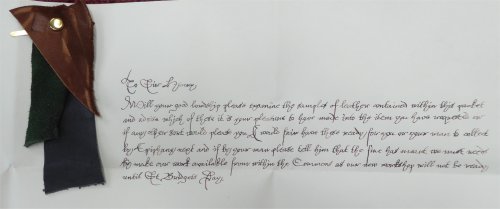

The idea was to direct those who read it to an area near the Commons at Faire, from whence they might spot the washing line and figure out how to convince the Laundress to hand over the items. I wrote some potentially useful ad lib chatter for the Laundress to deliver: The first lot of questers to spot the washing promptly absconded with the lot! When they brought them to me, I asked if they'd spoken to the Laundress and bade them return the clothing and seek out the good lady. Ref: Rawcliffe, Carol; Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities; Boydell Press, 2013 Letter from a Leatherworker

The letter, in secretary hand, noted that the item would be ready for collection by Epiphany (January 6), adding that a fire had meant it needed to be collected from within the Commons. This was a pointer to the area where the item could be found, hopefully by matching one of the attached leather samples with something on display (ie a batch of leather goods hanging in the Artisans’ area). In the end, the item turned out to be a document roll. Illuminated Manuscript Cardinales with hattes rede Book of Days Extract Certain Items Mislaid

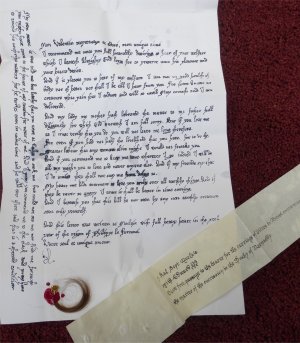

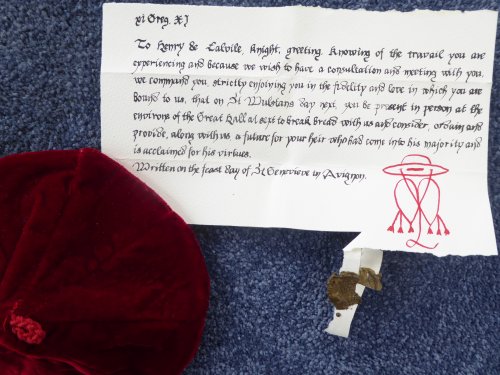

The letter notes that these would be left at the CF Market Cross but didn’t state a date or time; a market wallet (hand-sewn by Mistress Aliena de Savigny) provided a suitable receptacle for holding these. The letter's romantically red ink is rose-scented, which I purchased in Florence from the Il Papiro paper and calligraphy merchants, and entirely appropriate for the nature of this correspondence. The Cardinal’s Summons Langham had the interesting distinction of becoming Archbishop of Canterbury on two separate occasions (!), as well as Chancellor and Treasurer of England, but his appointment as Cardinal saw him fall out with Edward III, so he shifted to the Continent. From 1368 to his death in 1376, he was based in Avignon, where Pope Gregory XI was residing. The wording of the summons is based on some 1295 examples of Edward calling the three estates to Parliament, with a subtle reference to the soon-to-be acclamation of Hugh as a Laurel. The mark is based on a cardinal's sign being the hat and cords associated with the princes of the Church. To Henry de Calvile, knight, greeting. Knowing of the travail you are experiencing and because we wish to have a consultation and meeting with you, we command you, strictly enjoining you in the fidelity and love in which you are bound to us, that on St Wulstan’s day next following Cathedra Petri, you be present in person at the environs of the Great Hall at sext to break bread with us and consider, ordain and provide, along with us, a future for your heir who had come into his majority and is acclaimed for his virtues. Written on the feast day of St Genevieve in Avignon.

Nico was an immediate thought to play the helpful Cardinal, instrumental in the rearing of the foundling. I told him to think of Cardinal Richlieu from the Three Musketeers (the Charlton Heston role), which seemed to appeal to him. The Cardinal’s role in the Quest was to provide some of the most obvious clues as to the identity of the foundling, depending on what the questers asked, and so had to come towards the end of the quest period, hence the precise dating of his appearance: St Wulstan’s Day is the 19th of January, as marked in the page extracted from a Book of Days; sext being midday. I made a notice about the Faire bells being rung on the half-hour this year, slipping in the info that that would be ringing the hours including tierce, sext, nones and vespers spelling out when those were. One of the questers noted that she read that notice a couple of times while waiting in the lunch queue before she clicked as to its import. Thus Cardinal Langham was to lurk in the Great Hall around lunchtime, wearing a red velvet zucchetto, which I made, and sash (a borrowed baronial officer's one), and black robes, identifying himself as a Prince of the Church. The Cardinal had a pouch (made by Mistress Rowan Perigrynne) to hand over, containing the monies saved for the foundling (coins made and gifted by Master Brian di Caffa), as well as a couple of additional hints to drop as to the foundling’s identity if needed. He was allowed to be bribed or flattered into dropping more hints about the identity, but with the immediate serious injunction to keep such matters privy until the man himself may be told of his heritage, as it may be a bit of a shock. Such as: Particularly well-playing questers were permitted to be told that the foundling had just been recognised as Master of his trade (Hugh's elevation had happened by that point). The DenouementBy the time the Half-Circle Theatre rolled round, the questers had coalesced into two teams, one of which had found almost all of the items on the inventory; the other had concentrated on the identity of the foundling and identified him first. One of the truly amusing things was that the identification process for both teams seemed entirely logical to them, and completely left-field to me – a combination of guesswork, mis-reading and alternative interpretation produced the correct result! Thus one read the name tag’s mention of “my mother gave me no father’s name” as meaning that the foundling did not have a surname as such, but possibly a placename; the wording was taken from one of the period tags and wasn’t intended to be any such pointer. However, such reasoning did point to Hugh de Calais! The mention of the Captain was taken to mean that a port city or sailors were involved, which identified Calais early on for one group. But that reference was to the Captain of the Calais garrison, nothing to do with anything maritime.... We finished the Half-Circle Theatre with this announcement: As the final item of business at this gathering, we turn to the Last Will and Testament of the late Sir Henry Calvile, the collection of his far-flung inventory of goods, and the identification of the heir to his worldly goods. Firstly to the inventory. If you have them, please bring forward the following items:

As for the Quest for the Heir. As many of you will know by now, some 33 years ago, when he was but a lad, Sir Henry had a son by a Breton girl, who sadly died in giving birth. Sir Henry’s friend Simon Langham, now Cardinal Langham, took the babe and left him in the keeping of Cistercian monks in Avignon. There he grew into a strong and healthy young man, recently recognised as a master in his trade, but unaware of his heritage. Unbeknownst to father and son alike, they both came to reside in the same city, but sadly never met.

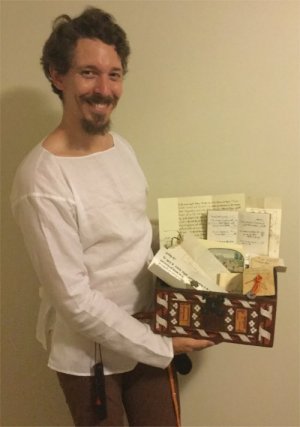

Many of you puzzled over the items in the coffer, piecing together the information that would identify Sir Henry’s heir, quizzing the Cardinal, the Magister, even Sir Henry’s innocent Laundress, amongst others. Some of you found out when the foundling was born, to whom; how he was described; in what city he dwelt, and slowly the clues fell into place. I then called upon the team who had made the first correct identification to fetch the foundling forth to receive his inheritance and all these items so lovingly crafted and carefully collected. Hugh told me later that he, like everyone else, was looking around the audience expecting to see some further theatricals -- perhaps multiple heirs duelling over the loot. When the questers took him by the arms and propelled him to the stage, he was dumbstruck, even more so when it dawned on him that we were utterly serious about him receiving his inheritance, gifts of affection and respect from friends and Laurels. He said: I've never been quite so overwhelmed in my life And in closing the Quest and the Theatre: For Master Hugh de Calais, born on St David’s Day AS 18 known as the year 1376 the 49th year of Edward III’s reign, resident of Calais, member of the Company of the Staple, recently admitted to the Order of the Laurel and now recognised as heir to Sir Henry de Calvile, late of the parish of Calais; great-nephew to Sir Hugh de Calveley, Captain of the Calais garrison, three cheers. Hip Hip Huzzah! Other peerage elevation entertainments here.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||