|

|

G13 : Materia Medica CabinetA&S Challenges: Stuff Other A&S Challenge Topics Throw physic to the dogs; I’ll have none of it. I keep a small collection of materials to assist in the health of those around me with simples and tisanes and the like. Such knowledge I have from the older folk and a few texts from the ancients recommending treatments, though some of these be more effective than others.

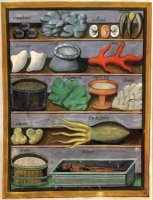

I have long wanted to do a cabinet of curiosities or wunderkammer, and have been collecting items for it (a cowrie shell, some bones and fossils and suchlike). Lacking a highly fancy cabinet or spare room to devote to this, the plan has lain dormant for a number of years until the Baronial Challenge combined with a chance flick through Umberto Eco's The Infinity of Lists (Maclehose Press, 2009). Illustrations (pg 179, 235) showed small collections in something akin to a modern shadow box; I had had one of those sitting under a table for many years just waiting for the right project.... So here is a collection primarily of materia medica, to match Gubbins Challenge 13. It is modelled after the 1470 rendition of the material collection in the Book of Simple Medicines, a manuscript written by Salerno physician Matthaeus Platearius. The box is accompanied by writings covering the medical knowledge associated with each material, held together by a leather point, as was common practice: in Jan Gossaert's Portrait of a Merchant (ca.1530) you can see documents strung together with a point and hooked on a peg. A 1620 letter instructs that: yow bring with you...all letters & notes filed on a pointe...& by a pointe fastened the papers can not be lost. The Lapidary Shelf

Lynx stones were identified by the Greeks as petrified urine streams from the European lynx, partially supported by the fact that, when burned, they smell like cat pee. As such, they were considered an important ingredient in remedies against bladder stones. Isidore of Seville believed that the lynxes deliberately peed in sand to hide it from humans. Gessner in his 1565 De rerum fossilium, lapidum et gemmarum maximè, figuris & similitudinibus liber (A Book on Fossil Objects, Chiefly Stones and Gems, their Shapes and Appearances), called them belemnites, a term used this day for what are now known to be a fossilised section of a Triassic squid relative. Red coral was highly valued in period, often given to children for teething and spiritual protection (the Christ child is often depicted with coral beads or branches). Paracelsus, writng in his Dispensatory and Chirurgery, considered it full of power and virtue, good to quicken the phansie or imaginative faculty and preventing the mind from being infected with impurity, wickedness of vanity. White coral was also thought to have similar virtues and more, being cited in the Peterborough Lapidary alongside various recipes for oral cures. Coral is considered a plant, animal and stone! Cowrie shells have value in many cultures, with its shiny hard shell attracting admiration for use as monetary exchange or as amulets. Because they are born from the sea, like Venus, they have also be associated with lechery. Ammonites were thought to be snakes turned into stone by the 7C Saxon Abbess of Whitby, St Hilda. Whitby, as with other parts of the UK, is a good place for fossicking for these fossils – I got the large segment for the box from off the beach near Lyme Regis, on England’s Jurassic Coast. William Camden, in his 1586 book Britannia, mentioned stones which, when broken open, were found to contain “stony serpents, wreathed up in circles, but eternally without heads”. Fake snake heads were sometimes added to provide verisimilitude to the stories! Scribal Equipment

I admit not exactly medical, but such items as seals and wax were not uncommonly seen on shelves in period portraits The wooden inkwell and leather penner were very kindly made for me by the wonderfully talented Lord Ronan mac Briain, based on period examples. The penner has thistles embossed, along with my motto Amor Omnia. The ink is genuine sepia, bought at a stationers in Venice, along with the glass pen and seal; the latter has a double KK sigil and is the one I use for stamping personal letter. Red sealing wax for letters and a round of beeswax complete the shelf. I don’t know where that rat came from…but they do seem to follow me around. A Variety of Materials in a Variety of Containers

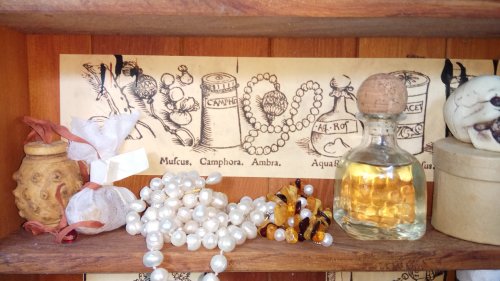

I was pleased to find the woodcut showing a batch of substances and how they were typically stored, and have done a reasonably close approximation with a bunch of stuff I happened to have to hand. The 1559 Salasin di Ascoli Compendiu Aromatarum notes the proper way apothecaries should house their items, using straight-necked glass jars sealed with pitch and wax over tied-on parchment cover. It also mentioned using stuck-on paper labels; pills wrapped in leather; herbs and powders in linen bags; and unguents in galley-pots (further research need on those!). The wooden pomander is one made by Master Edward Braythwayte based on a Mary Rose example. Not having any musk, I included some mulled wine sachets with assorted spices – cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg and cloves – useful to add to wine to cure cold humours. The large string of freshwater pearls was purchased at a Spanish market. I haven’t been game to try the various potions that start off by dissolving pearls in wine, vinegar or lemon juice! The print shows beads of ambra, and there is much debate as to whether that means amber, the well-known tree resin, or ambergris, the waxy product of whale digestion, highly sought-after as a perfume fixative. Pliny and others thought yellow amber highly useful. I’ve gone with that. The glass bottle contained aqua rosa (rose water); the lidded box has walnuts with a skull on top to remind us that Death is always with us Ref: Griffenhagen, George & Bogard, Mary; History of Drug Containers and Their Labels, American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, Pub No 17 1999 A Herbal Shelf

Herbs were the foundation of most medical treatments in period, and some were even effective. Whether as teas or poultices, in ointments or oils, long observation had provided some useful knowledge as to the properties of plants and what they might be used for. The practices of the likes of Avicenna and Maimonides were highly regarded and many herbals went through multiple copies and editions across Europe. The written material that goes with this Materia Medica includes the score of uses rosemary could be put to, taken from a Venetian treatise.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||