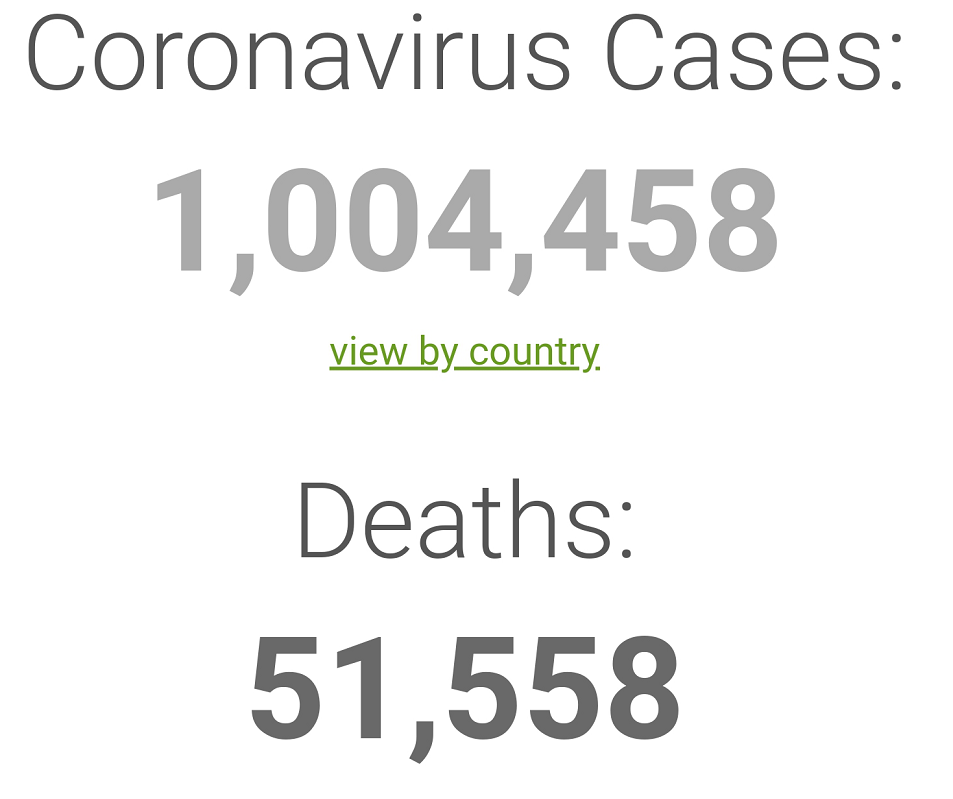

New Zealand shut the stable door after the Covid-19 horse had bolted, then set about reining it in. On March 26 the entire nation began a full-on, four-week lockdown. The country had 102 confirmed and probable cases, exactly one month after Italy had reached its own 100 mark and a mere three weeks after the USA did. In a world already inured to fast food, fast jets, fast computers and instant messaging, exponential virus time seemed to top them all.

In the early days the lockdown was a bit chaotic. The government got the basic messages out - "Stay home! Be kind! Don't pop your bubble! And also be kind!" - but then scrambled to iron out rules for a host of businesses who reckoned they were essential and churches, iwi, interest groups and individuals who thought they were special.

Kiwis grumped loud and long about their inability to surf, boat, hunt and tramp the lockdown away - walks confined to the local neighbourhood got old real fast. Or they fretted about the businesses and staff who were losing their livelihoods - at least for a time, but in some cases for good. Even so, they complied - Google's mobility website showed them going out less and staying home more than anyone else in the developed world. The government's declared aim was to eliminate the virus altogether, and the people would settle for nothing less.

At the end of week two, a media storm arose because the Minister of Health, early on, had driven his family 20km to walk along a beach. The reaction reflected the national determination to defeat the virus - with no holds barred and no quarter given to anyone who'd let the side down. The daily Covid-19 press conference at 1pm became compulsive viewing - checking the score, obsessing over the numbers in hospital and intensive care, or whether the nearest cluster was still growing.

Slowly, but surely - 89 new cases, 67, 54, 50 - the curve began to bend, even as testing was escalating to new heights. As the third week began, the confidence was palpable - we not only could beat this thing, we bloody well were beating it.

Some folk began lobbying for a rapid re-opening to save the economy, but wiser heads prevailed. "Four weeks means four weeks" - the remaining days were spent completing and then explaining plans for how the lockdown would end. And on April 23, end it did.

New border controls meant a mandatory two-week quarantine for all arrivals, extended as required for someone who tested positive. International air crew stayed in designated hotels they couldn't leave, except to fly again. New regulations mandated strict social distancing and enhanced cleaning and air filtration in all commercial premises, even as they were allowed to reopen. Gatherings of more than 50 people were banned for the duration. Protection for hospital and care workers was heavily beefed up, since experience had shown that their workplaces - outside of airports - were far and away the biggest sources of new infections.

For most people, some much-missed privileges returned - they could enjoy the outdoors again. They could attend funerals and weddings. They could gather in small, widely-spaced groups to spend time together. But some old ways didn't quickly return. Nightclubs and cinemas stayed closed. There were no concerts. Pubs, restaurants and cafes were tightly constrained by spacing rules - outdoor seating was really popular at first, but winter soon put paid to that.

As case numbers dwindled, testing shifted to surveillance mode. By now, only one test in 1,000 was positive - and vastly less when districts were randomly sampled to try and spot hidden community spread. To preserve testing supplies in a world still madly chasing them, samples were batched together 50 at a time for tests. It was far quicker and used way less supplies to test a whole batch at once. Only if it tested positive did they need to go back and do 50 individual tests.

Along with border quarantine and surveillance testing came electronic tracking, to speed up contact tracing. A simple phone app logged whenever someone's phone came within bluetooth range of another. This needed no mobile data, no location tracking, no central registry. If someone tested positive for Covid-19, their encrypted log was uploaded to a government server and within ten minutes all contactees got a message inviting them to get tested. The whole system was completely voluntary - but heavily spruiked by the "Opt in and win!" campaign, with its intentional double meaning. Sure, people wanted to beat the virus - but they also liked the idea of the weekly $20,000 draw for those who kept the app loaded and bluetooth on.

The Prime Minister took pains to explain all the protective measures: "we've got layers - like an onion". Arguments raged back and forth about extra layers, such as masks and other protective gear for the general public. In the end, no law was made but most people made and wore masks in public anyway - until Zero Day.

On Zero Day, June 14, it rained up and down New Zealand, with driving snow in the high country. But nobody minded. Outside of border quarantine, nobody at all had Covid-19 - not even in hospital. Surveillance testing now covered more than 50,000 people a day, spread right across the country - yet no new cases had turned up for a week. At 6pm, everybody watched the news then went outside. They blasted their neighbourhoods with horns and hooters, played their favourite music Really Loud, performed hakas and let off every firework they'd stashed in the back cupboard three Guy Fawkes' ago. In the rain.

The next day, the national Covid-19 Alert level dropped for the last time - from 2 to 1 - and stayed there for fifteen straight months until the vaccine arrived. There were several scares and five limited outbreaks, all picked up and contained within days.

The economy made a gang-busters recovery. Food and other exports soared, international students returned in droves and a surprising number of tourists - once they could get here - were willing to go through quarantine to visit a virus-free country for months at a time. Australian tourists dominated at first, especially after they also reached Zero and were exempted from quarantine. Supply lines, torn and stretched for so long, gradually recovered, and exporters soon started complaining about the high dollar. Just like old times.

Kiwis sat in their island nation, looking at the outside world with a ton of empathy, a lot of a relief, and more than a little smugness. They'd knocked the bugger off.